THE HANDS OF L'ARGENT

June 16, 2019 | Misc.

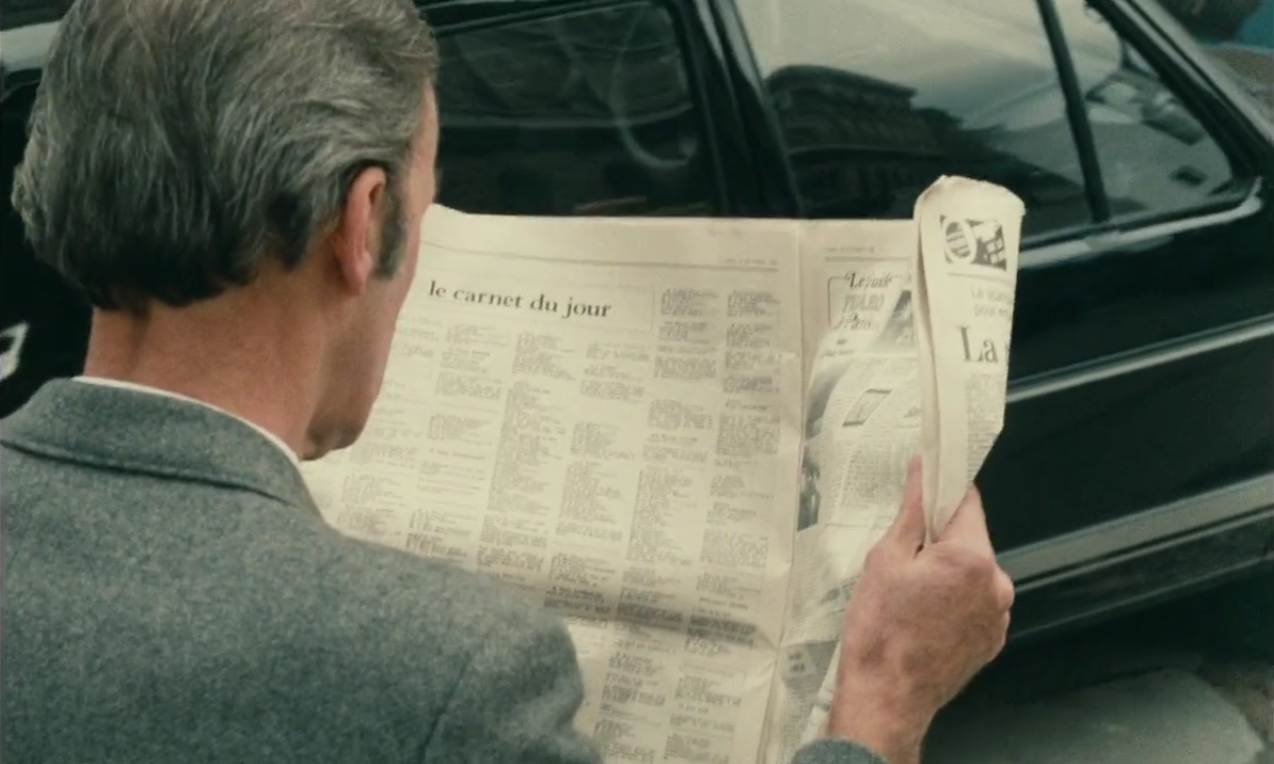

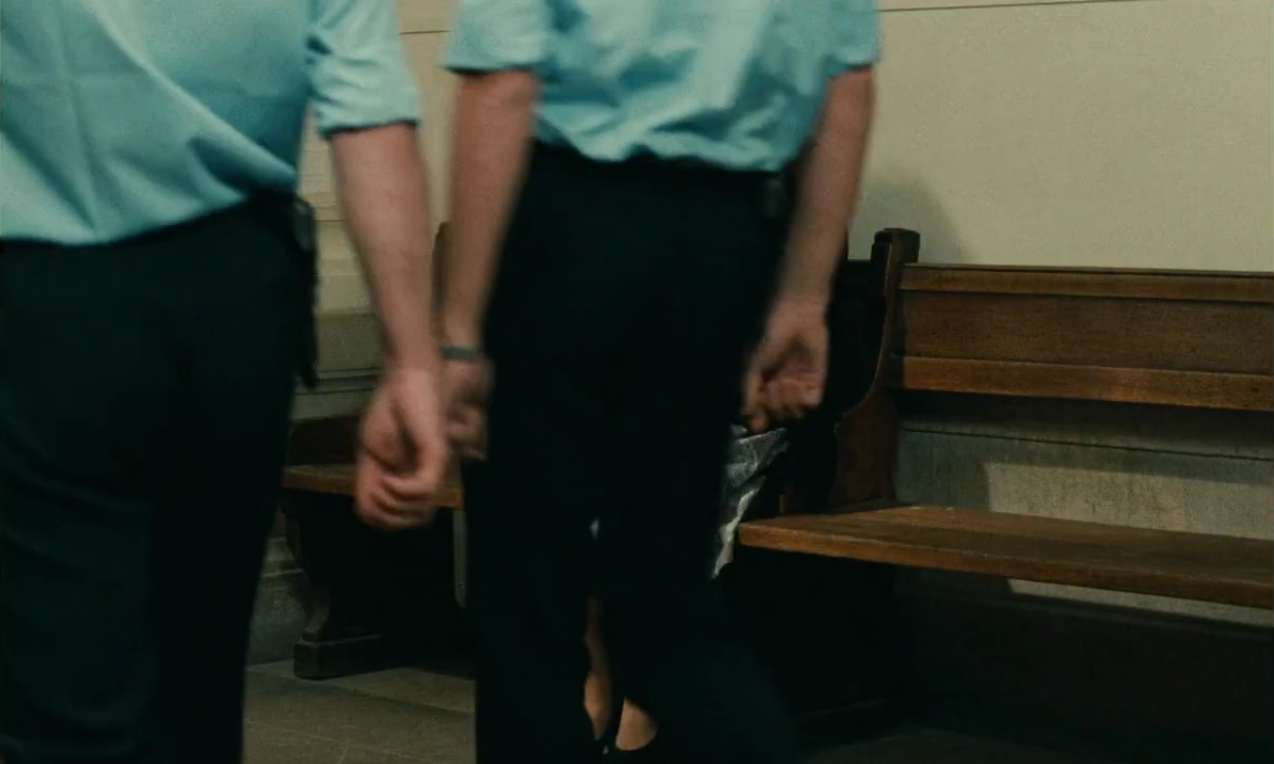

French filmmaker Robert Bresson (1901-1999) rejected the simple pleasures of cinema. He wielded a passive camera which flattened all and judged nothing, neither reducing nor enhancing any particular object beyond any others. He utilized a deliberately narrow and repetitive practice of cinematography so that no one type of shot or technique would ever stand out. He shot his actors—or as he called them, models—statically and from the chest-up, tracking only ever slightly and subtly, and edited with a blunt practicality. "No beautiful pictures," he wrote in Notes on the Cinematograph, "only necessary ones."

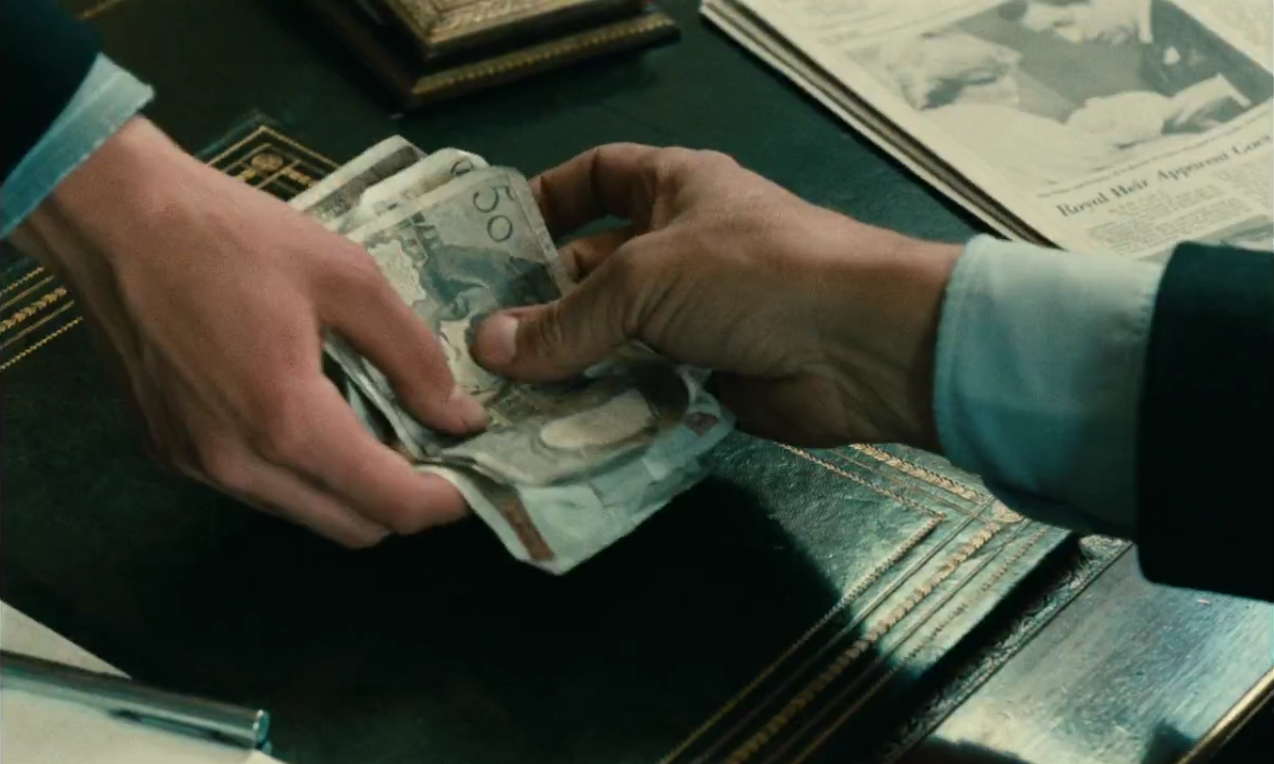

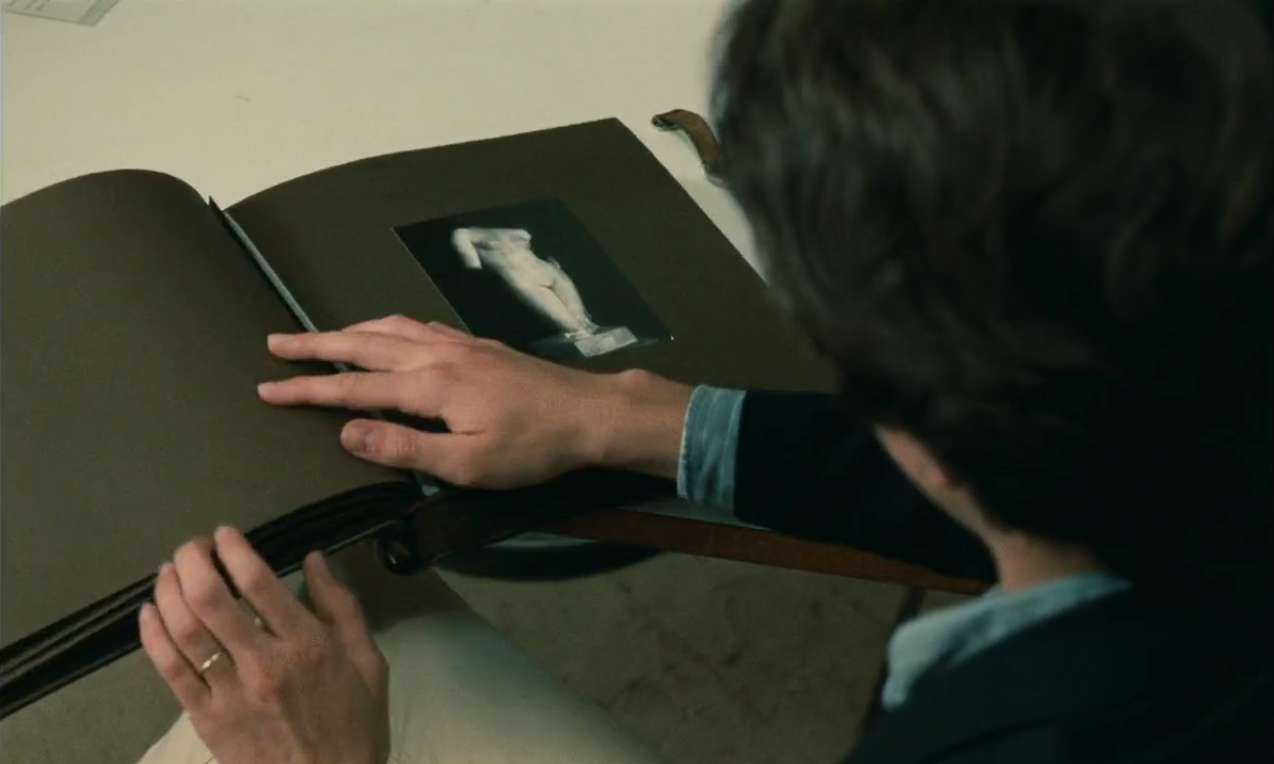

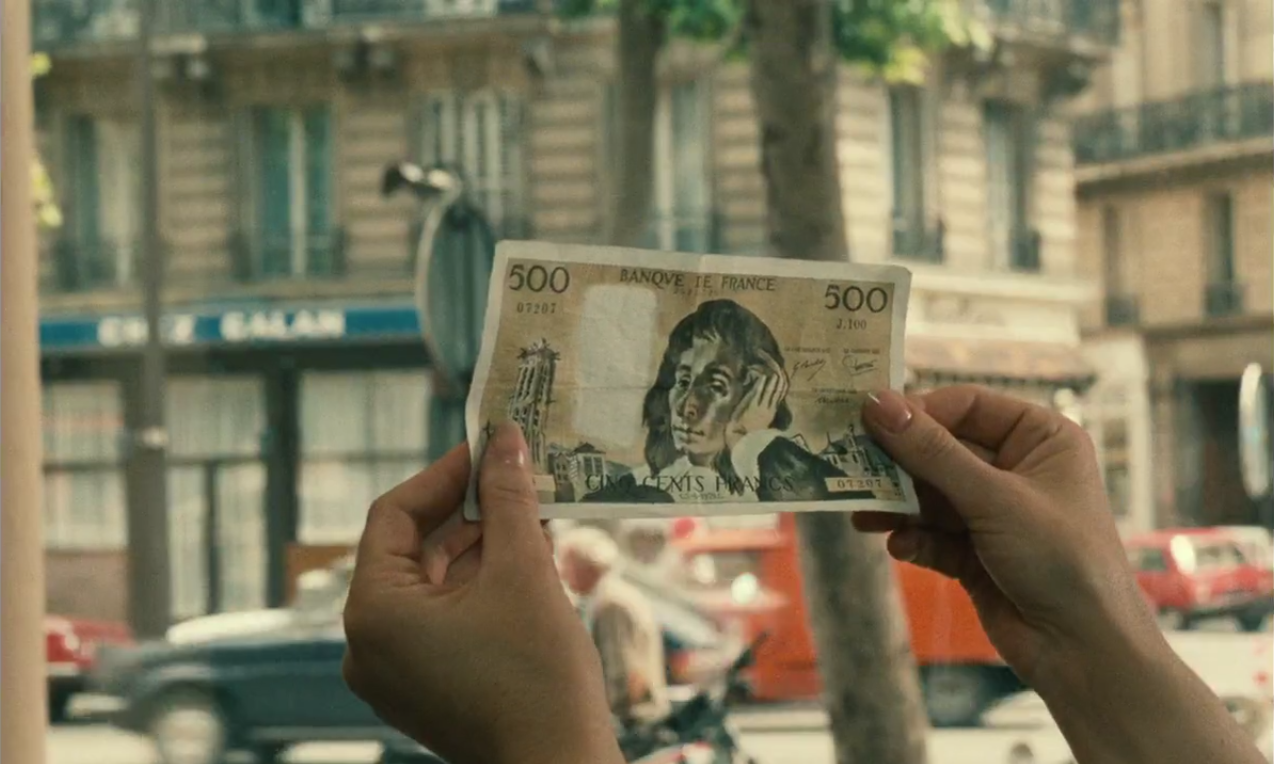

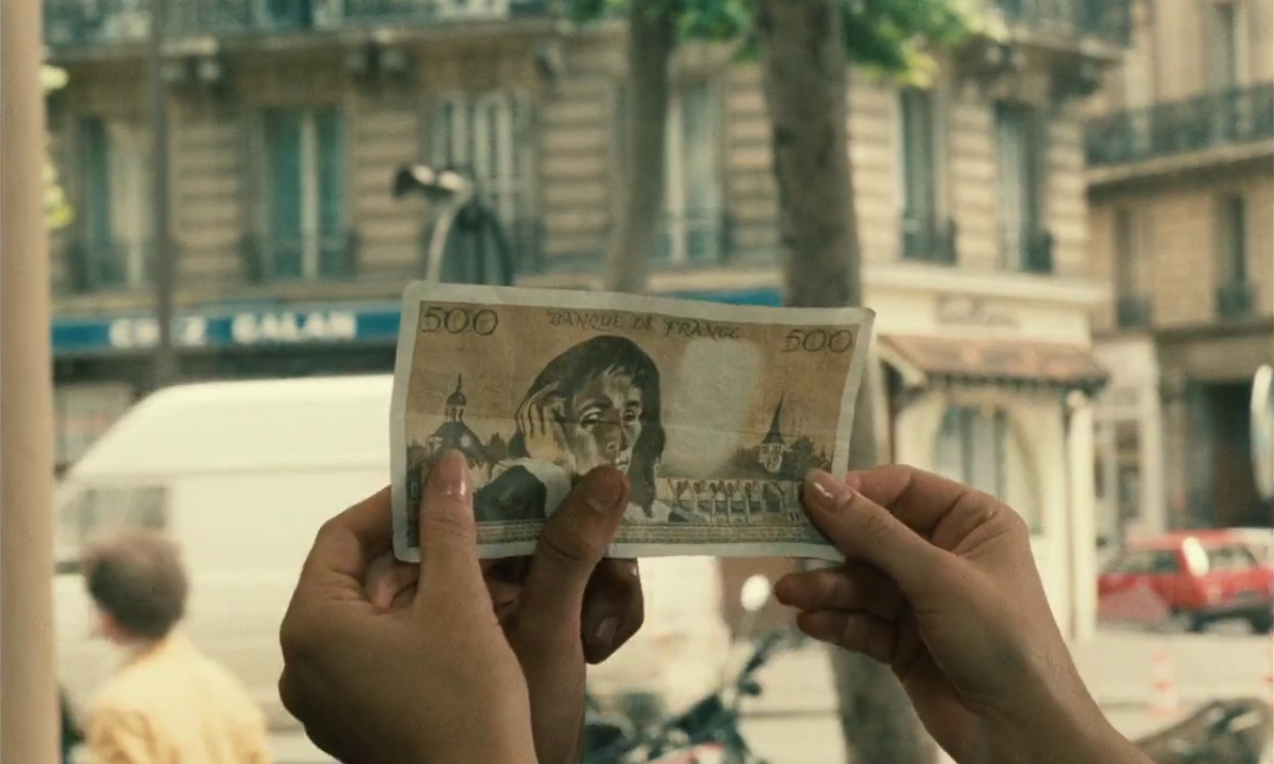

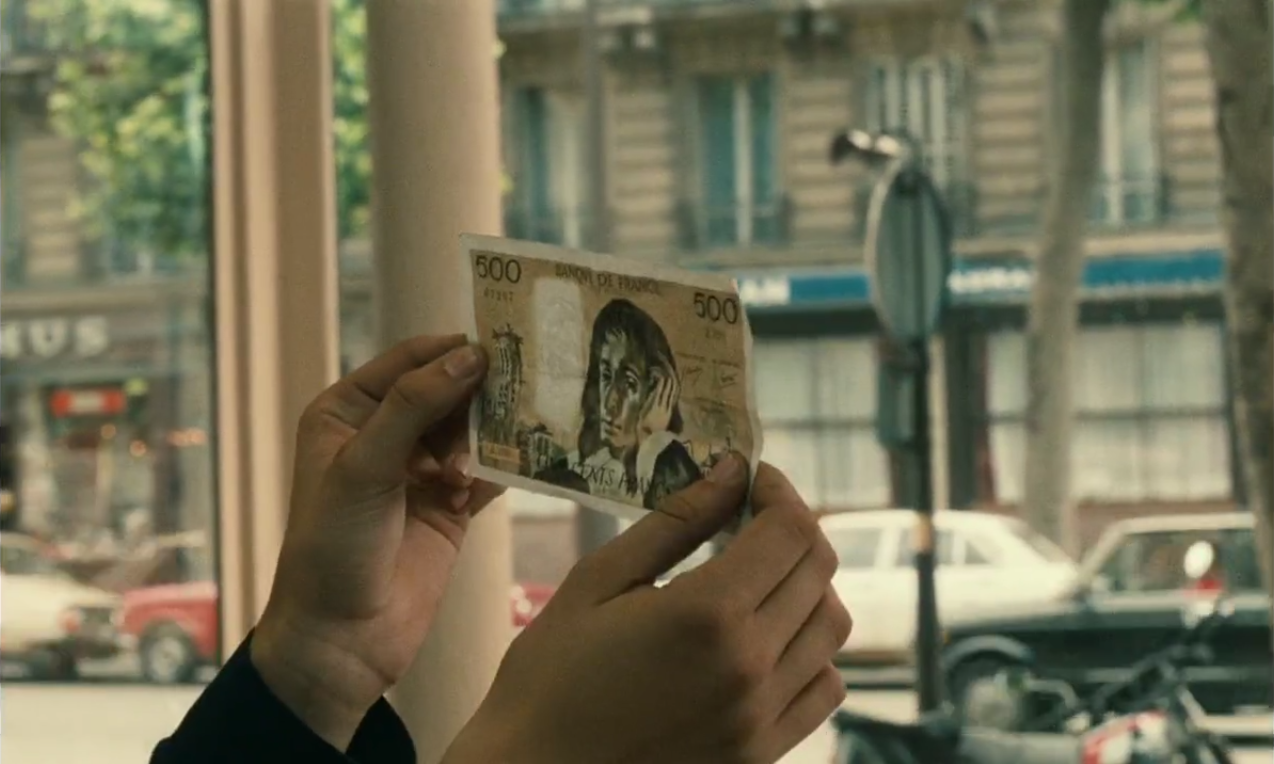

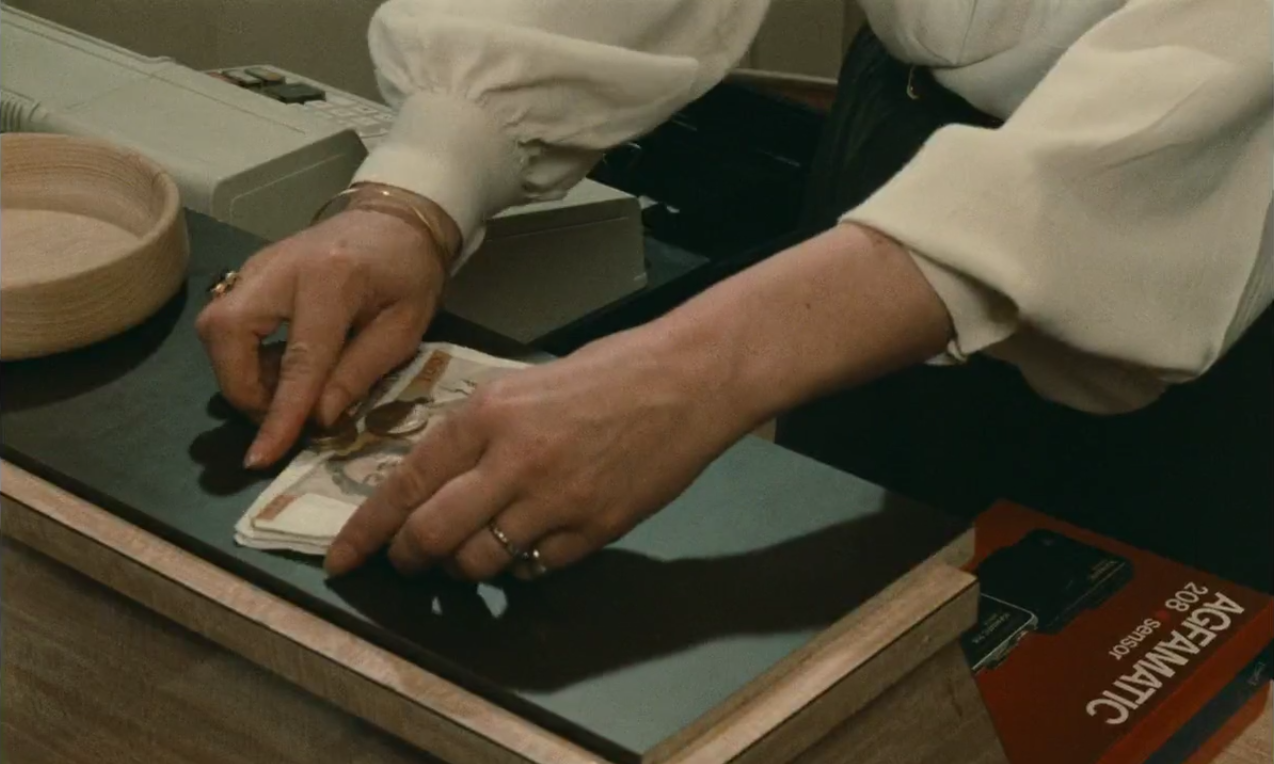

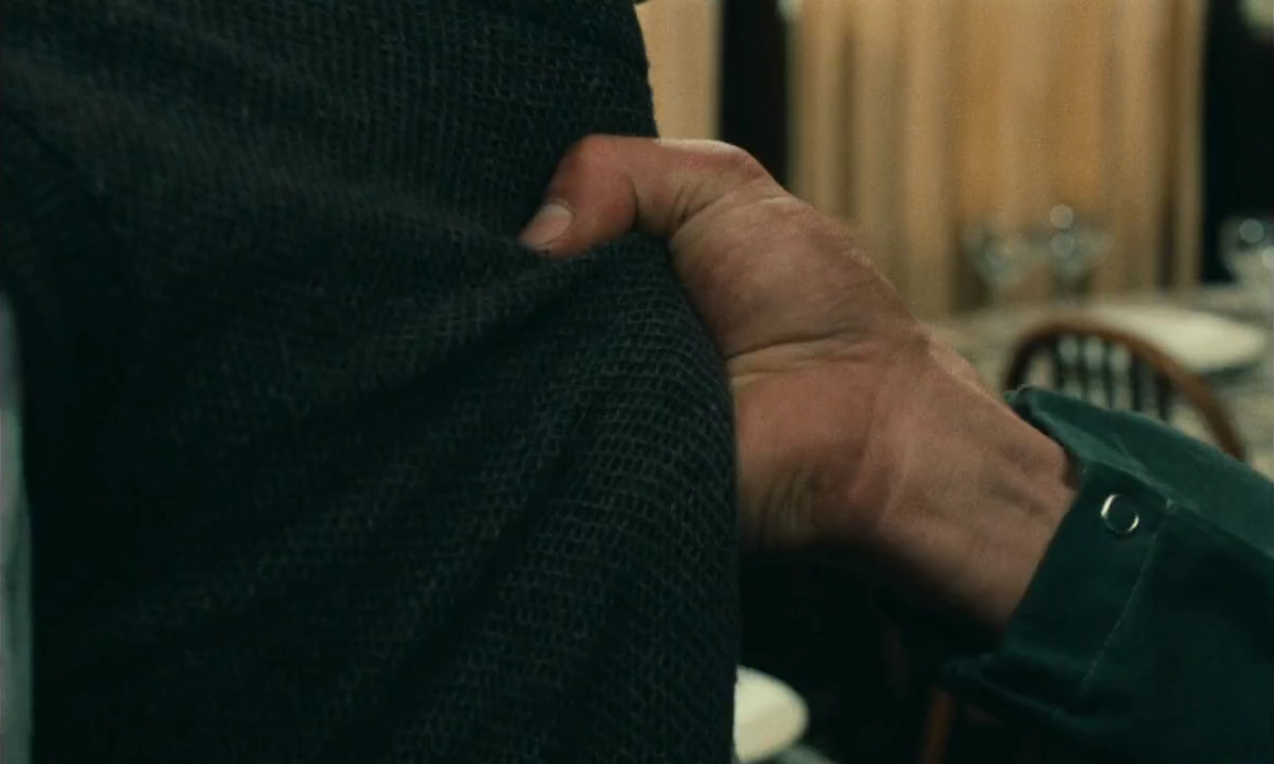

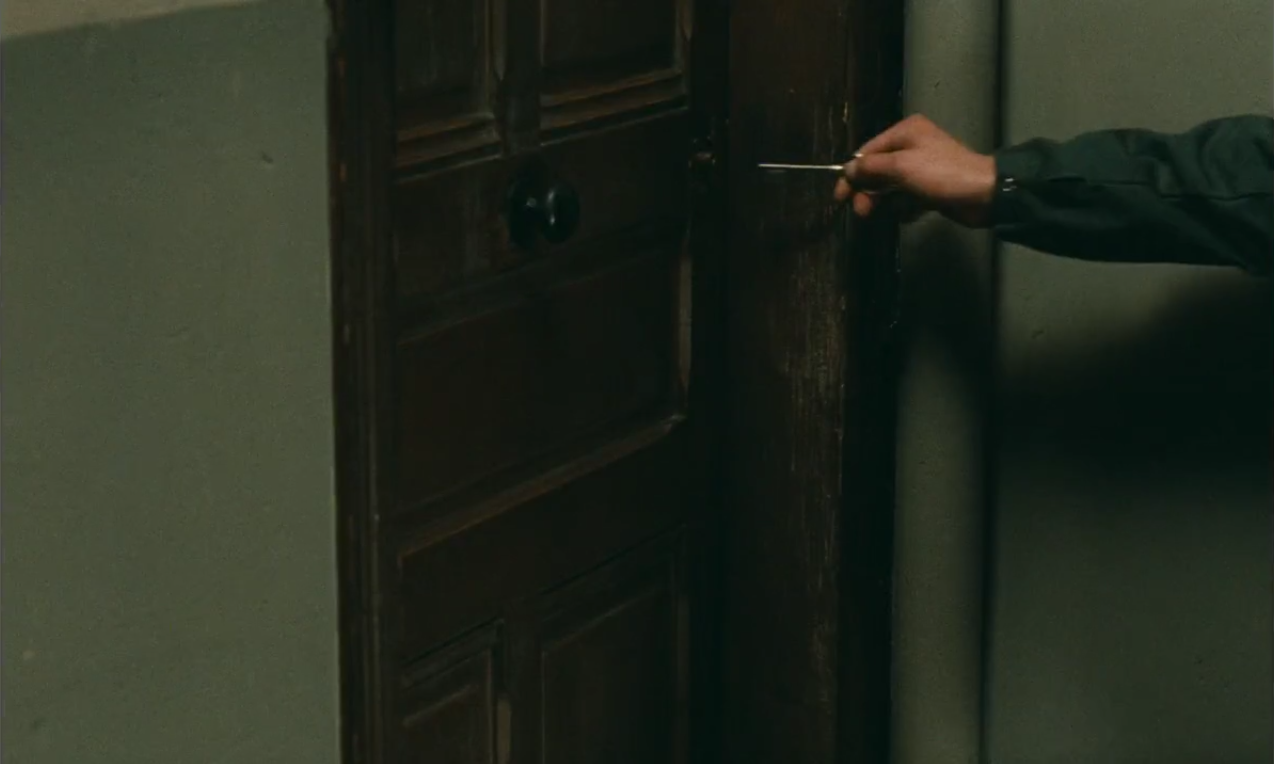

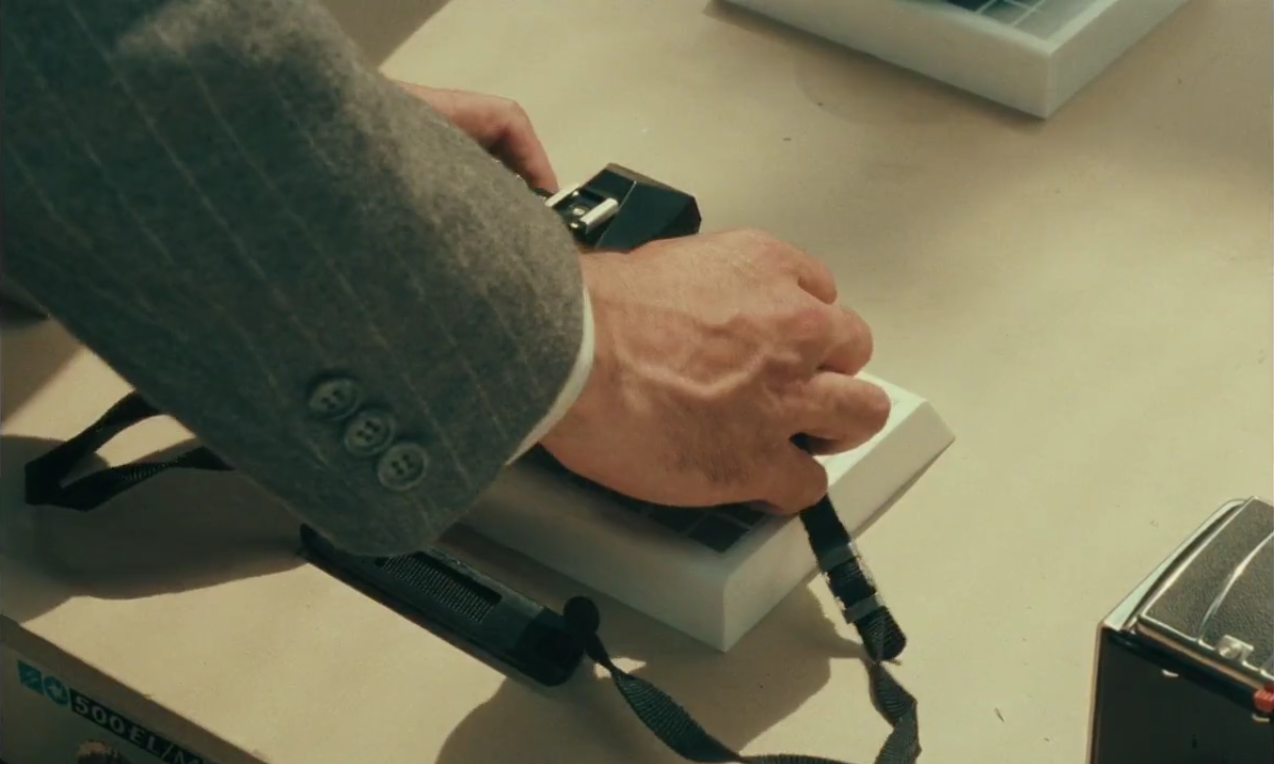

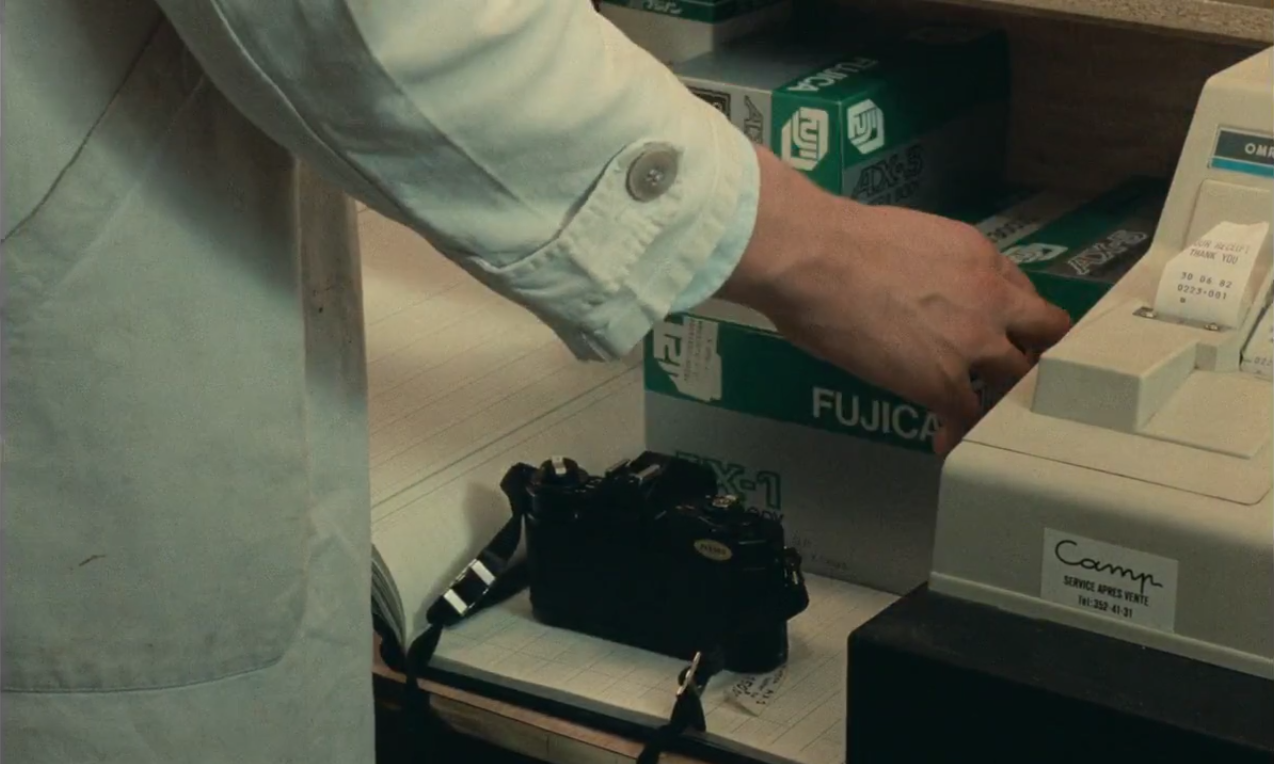

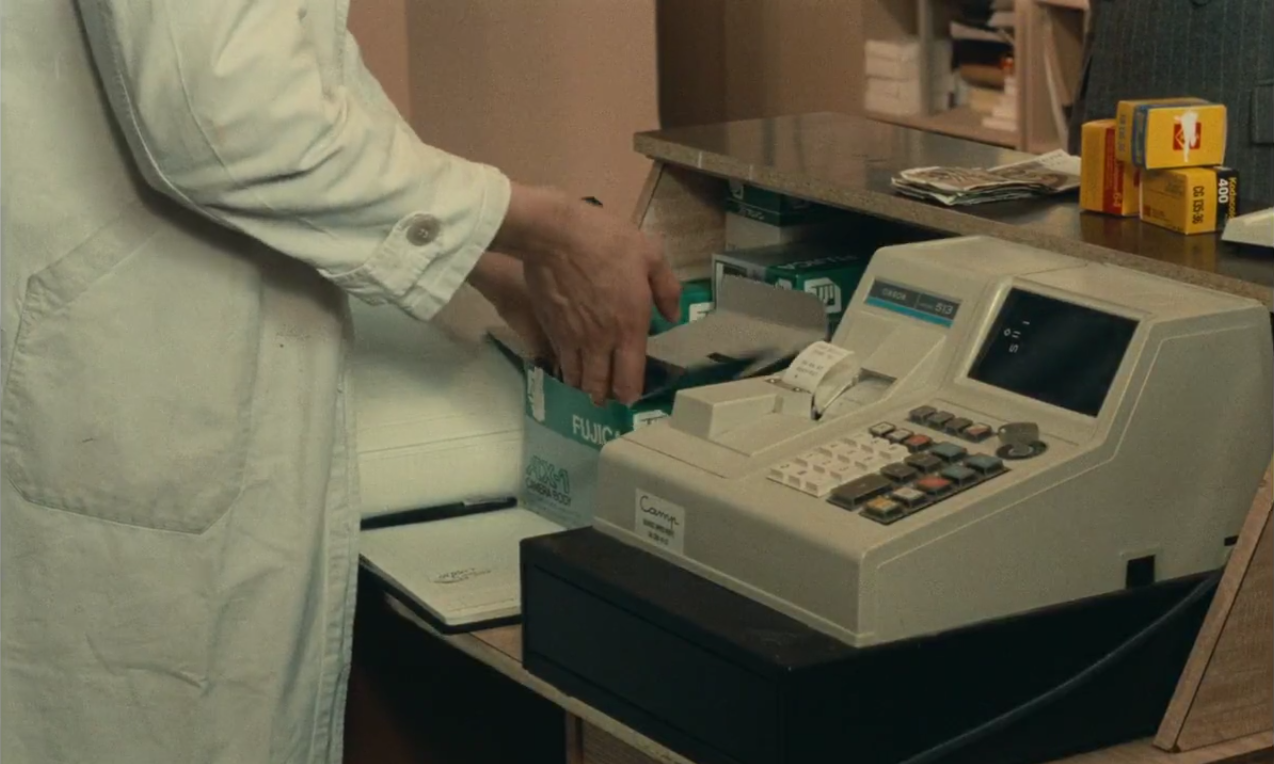

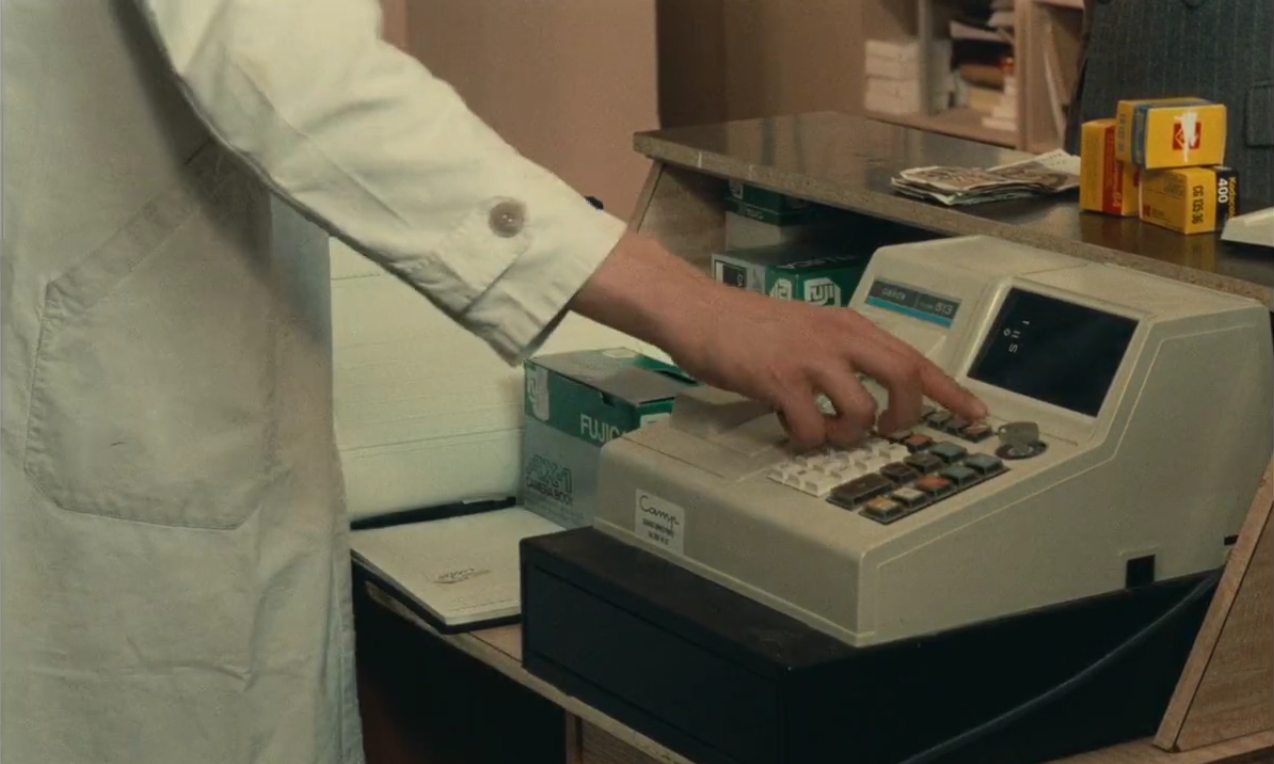

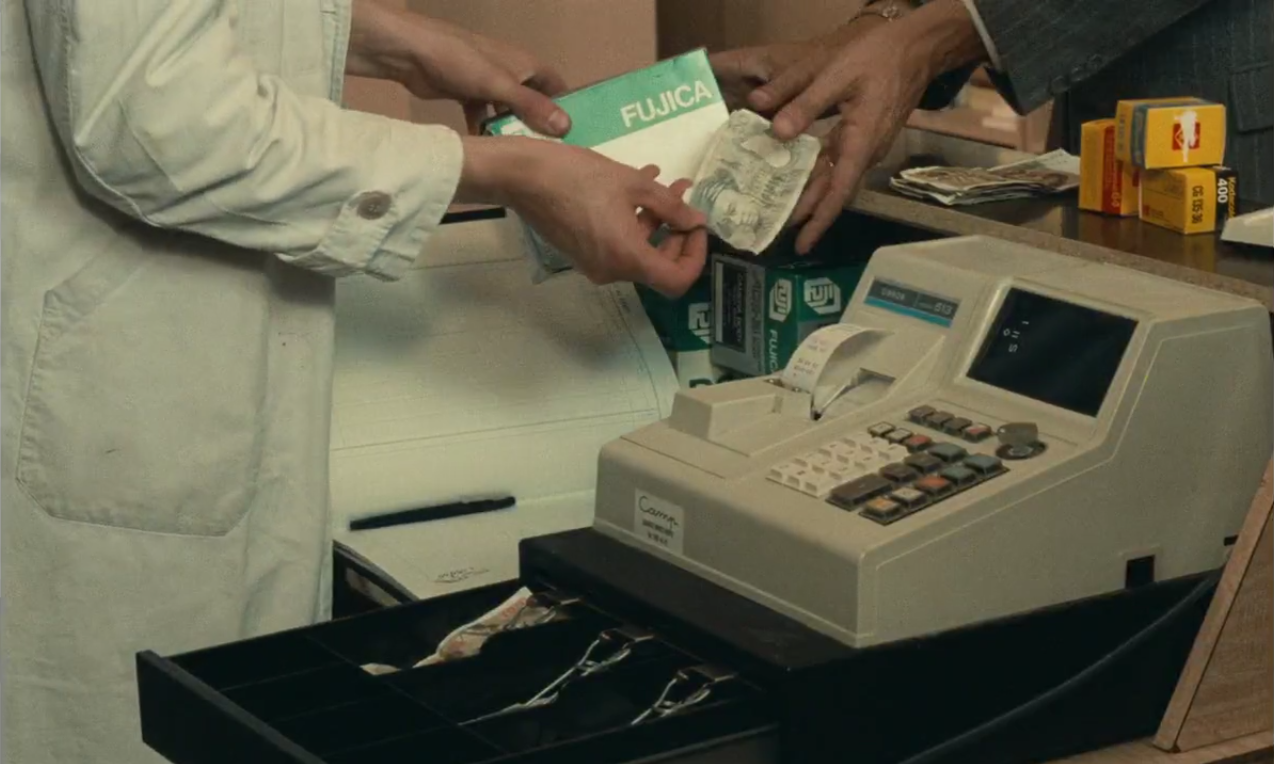

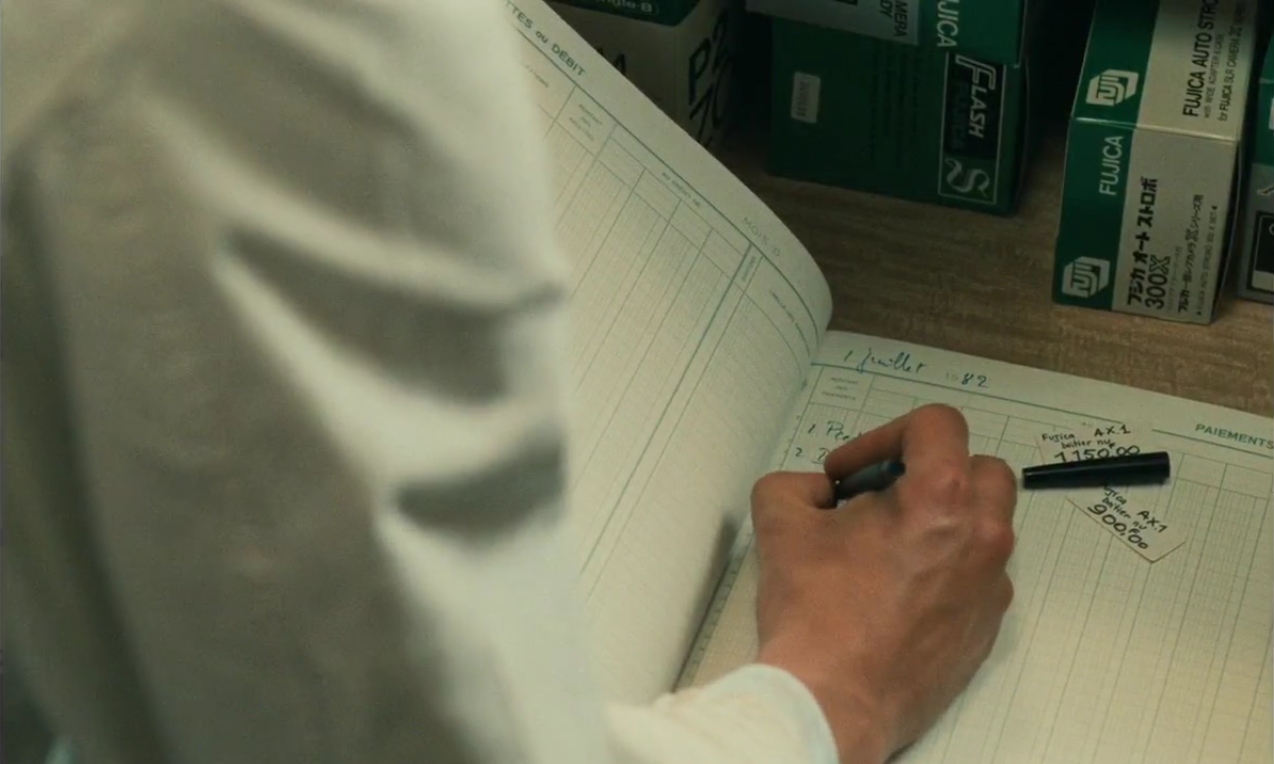

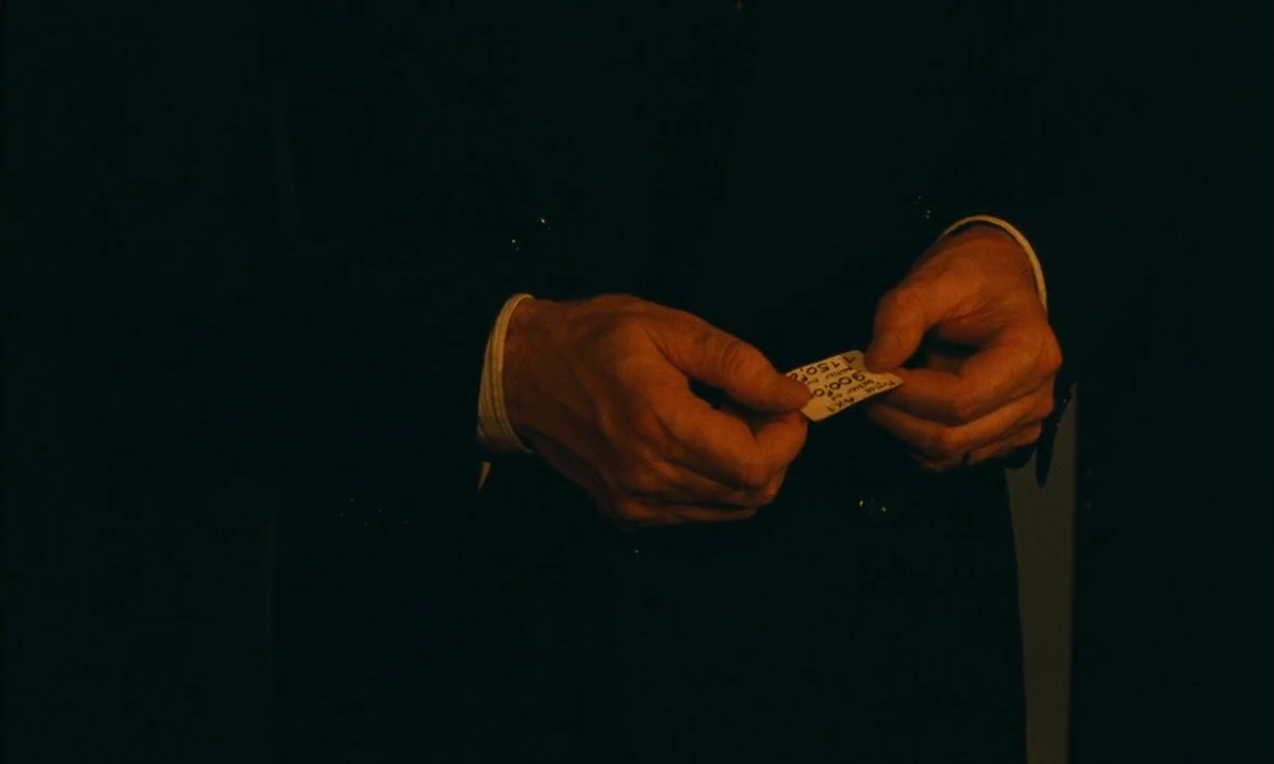

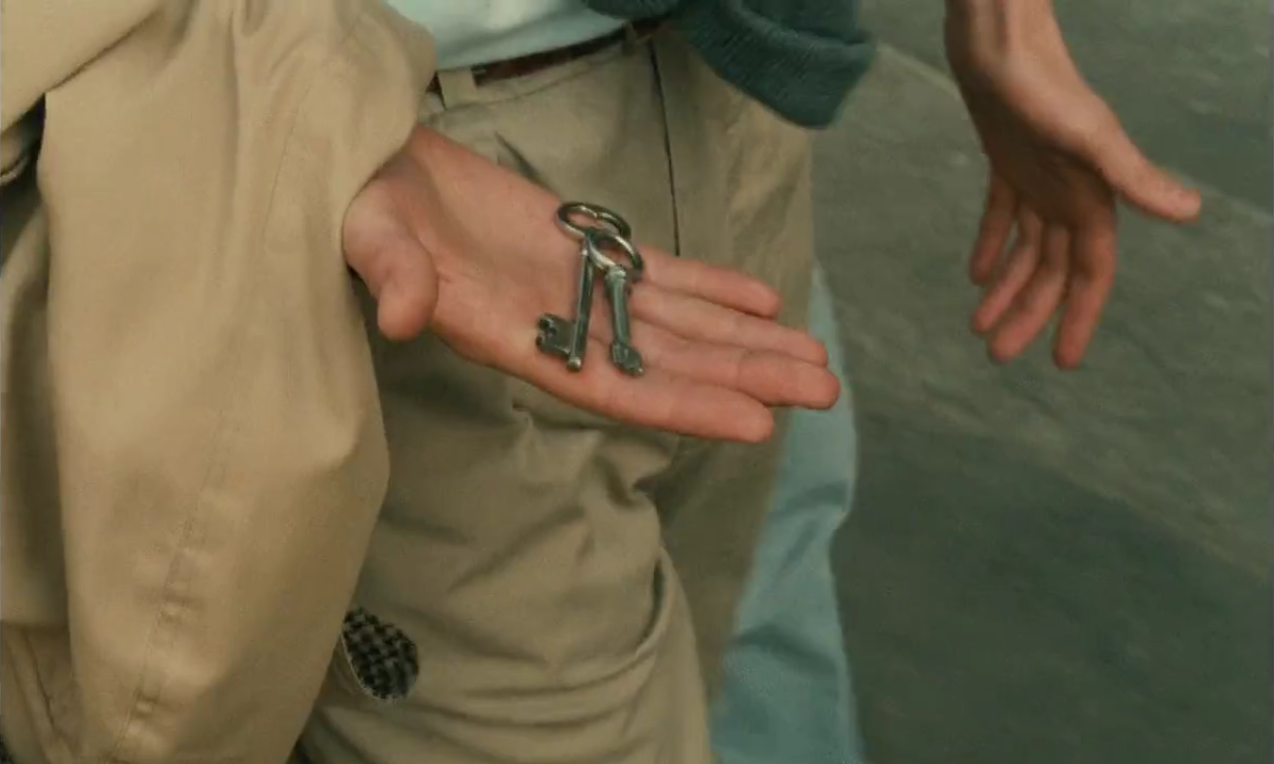

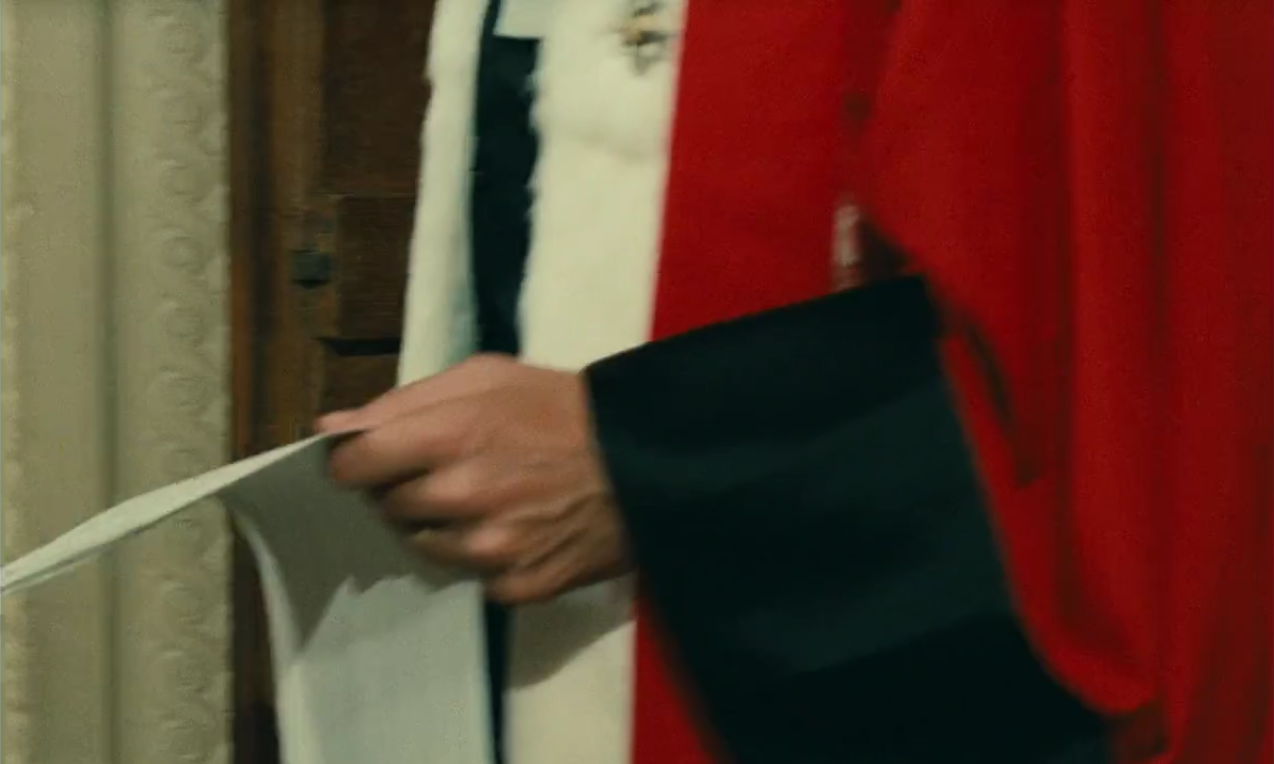

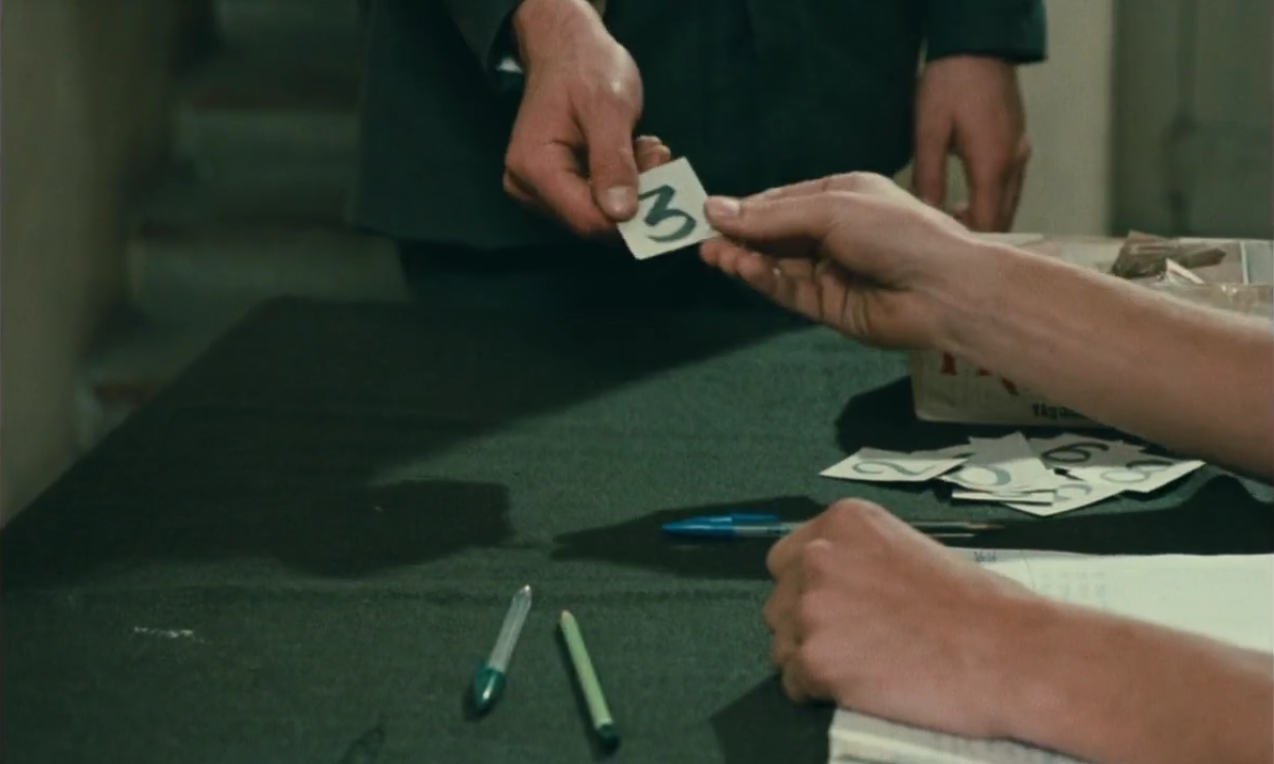

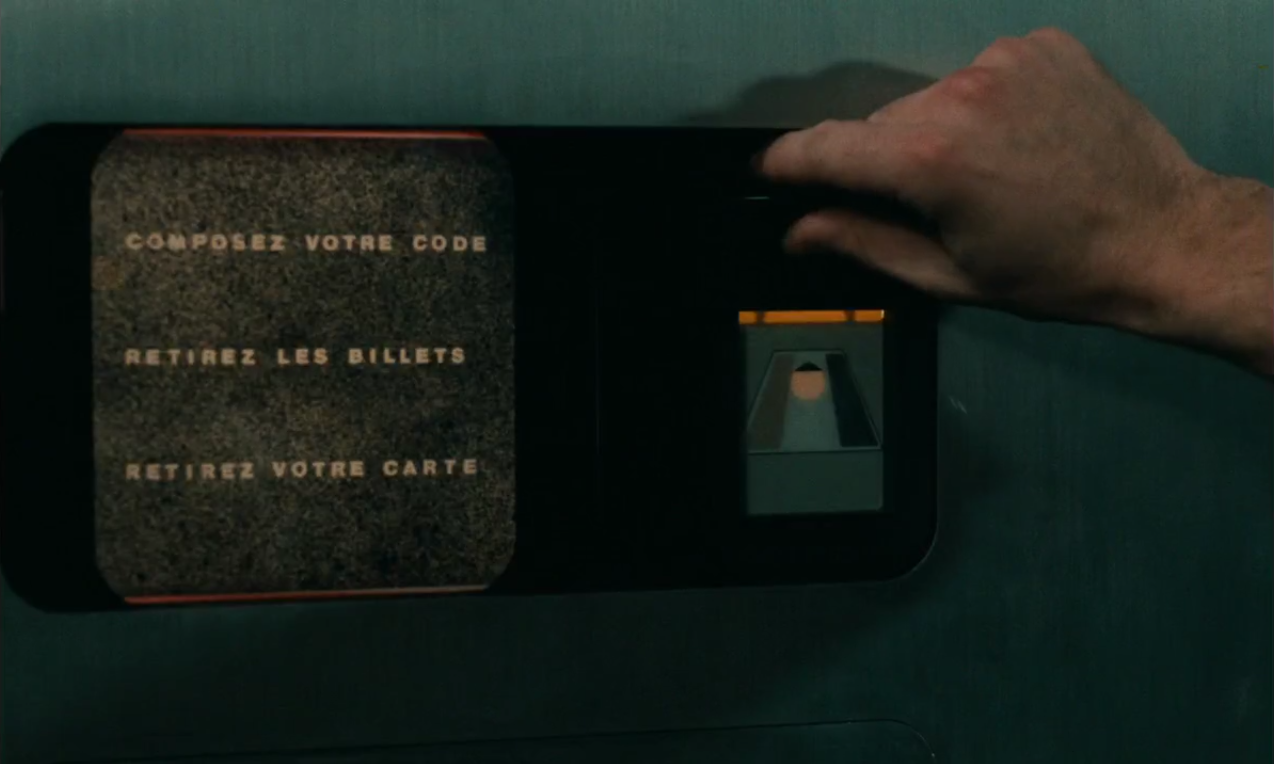

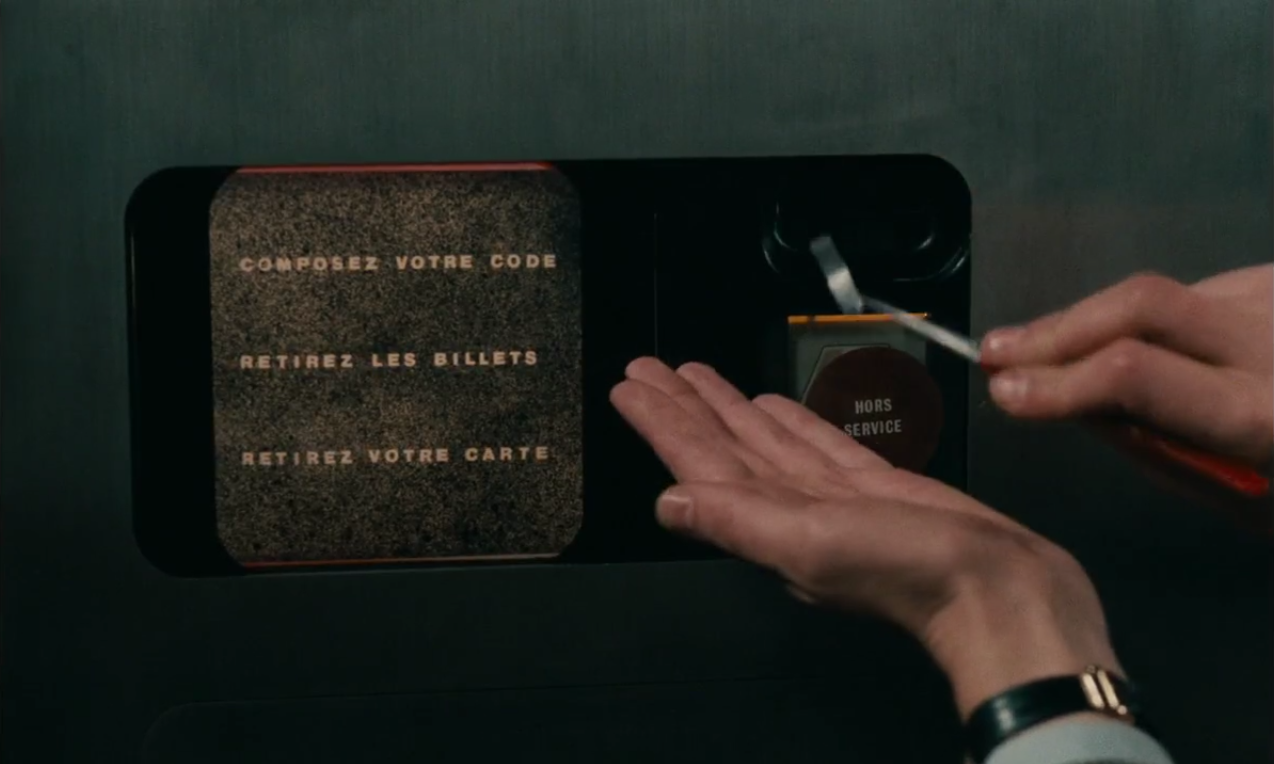

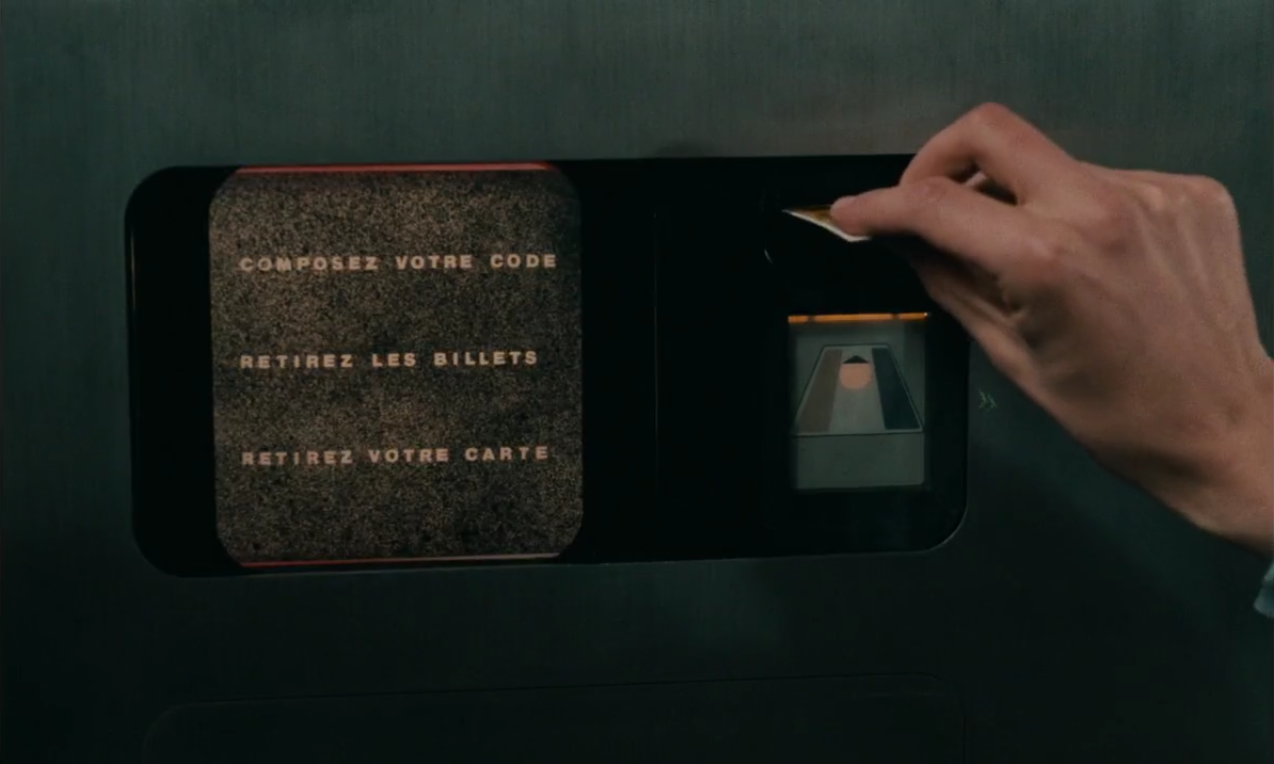

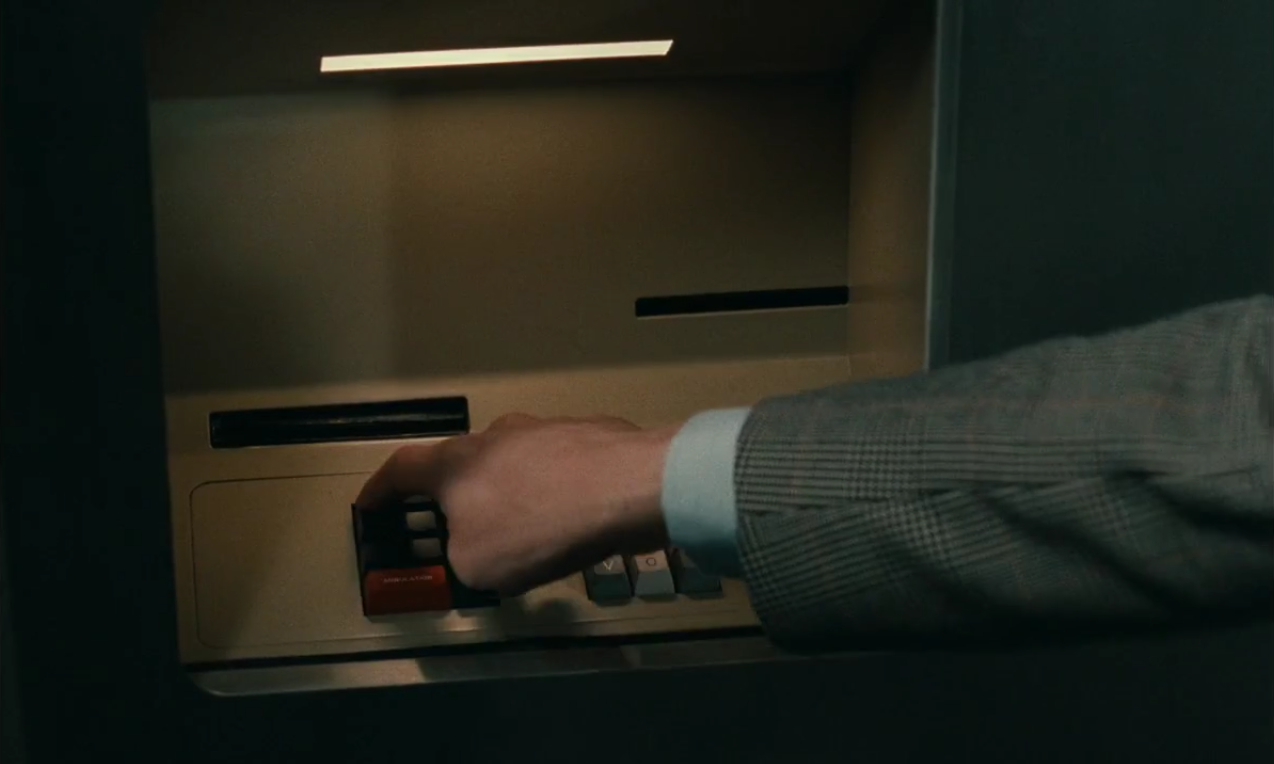

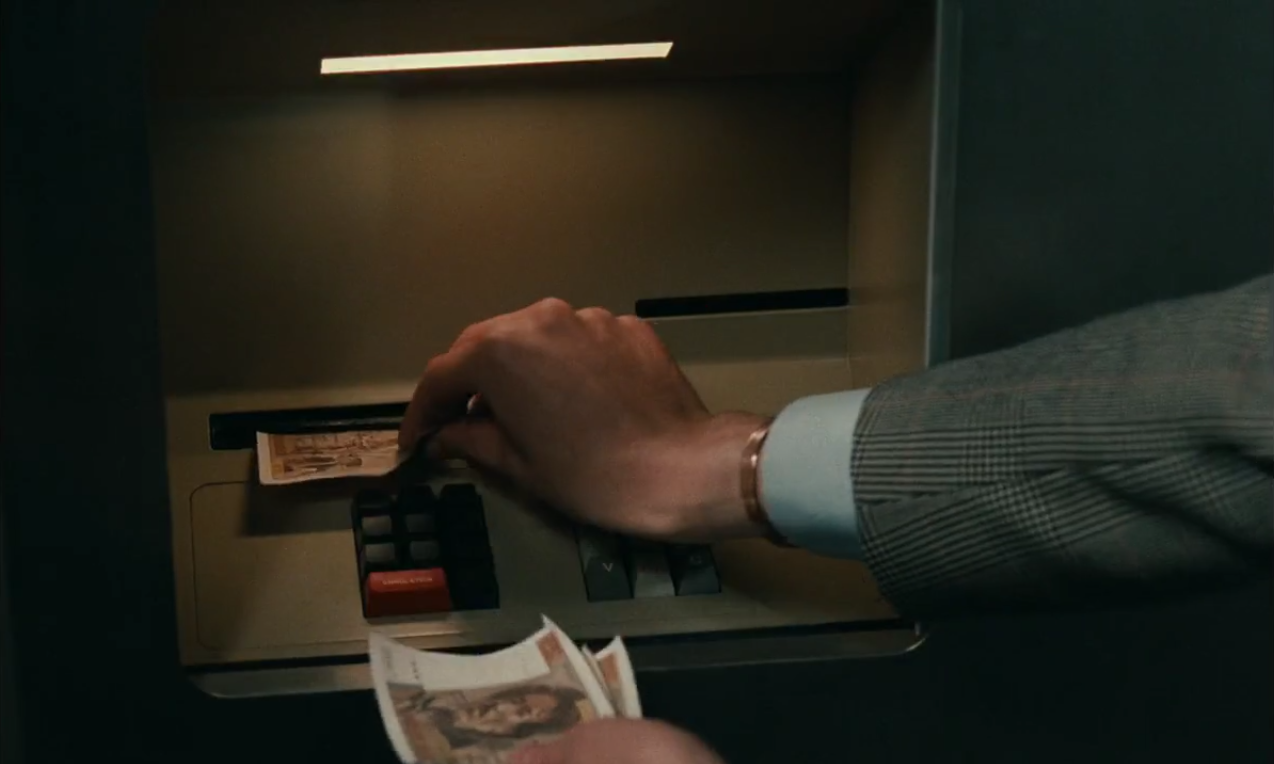

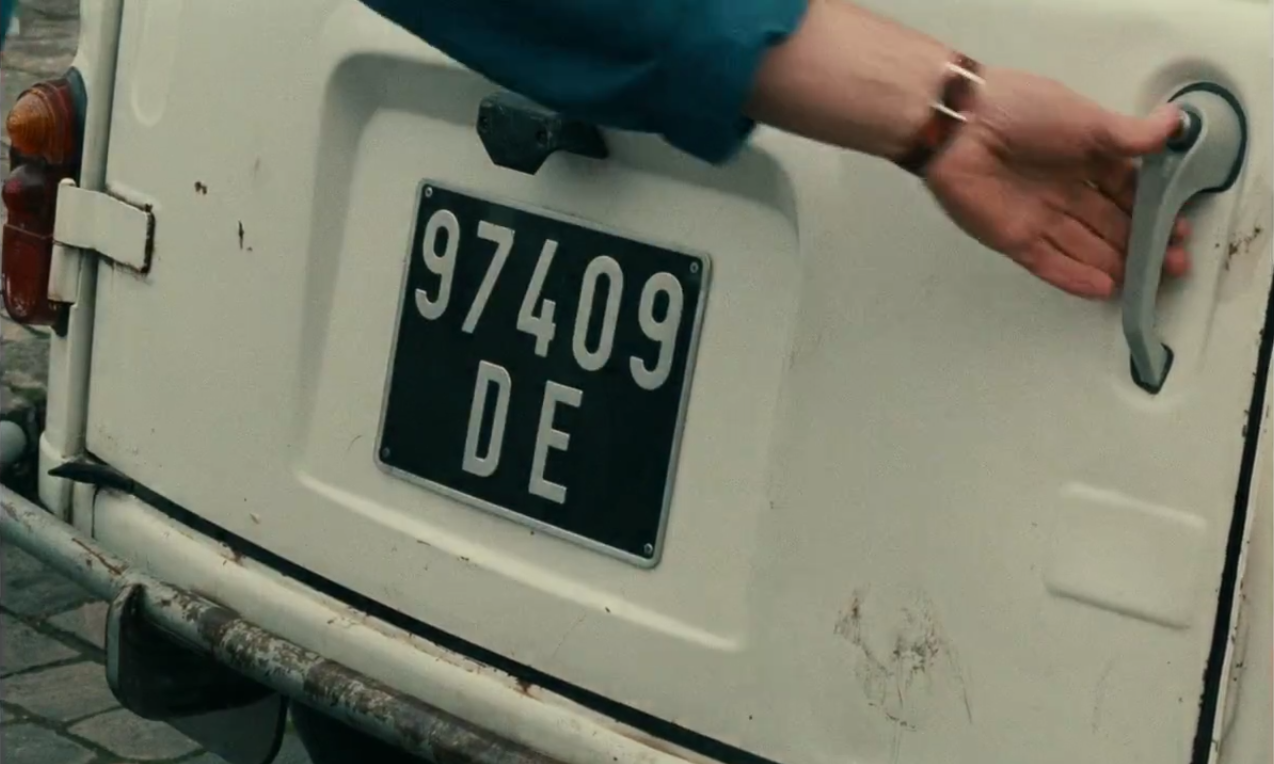

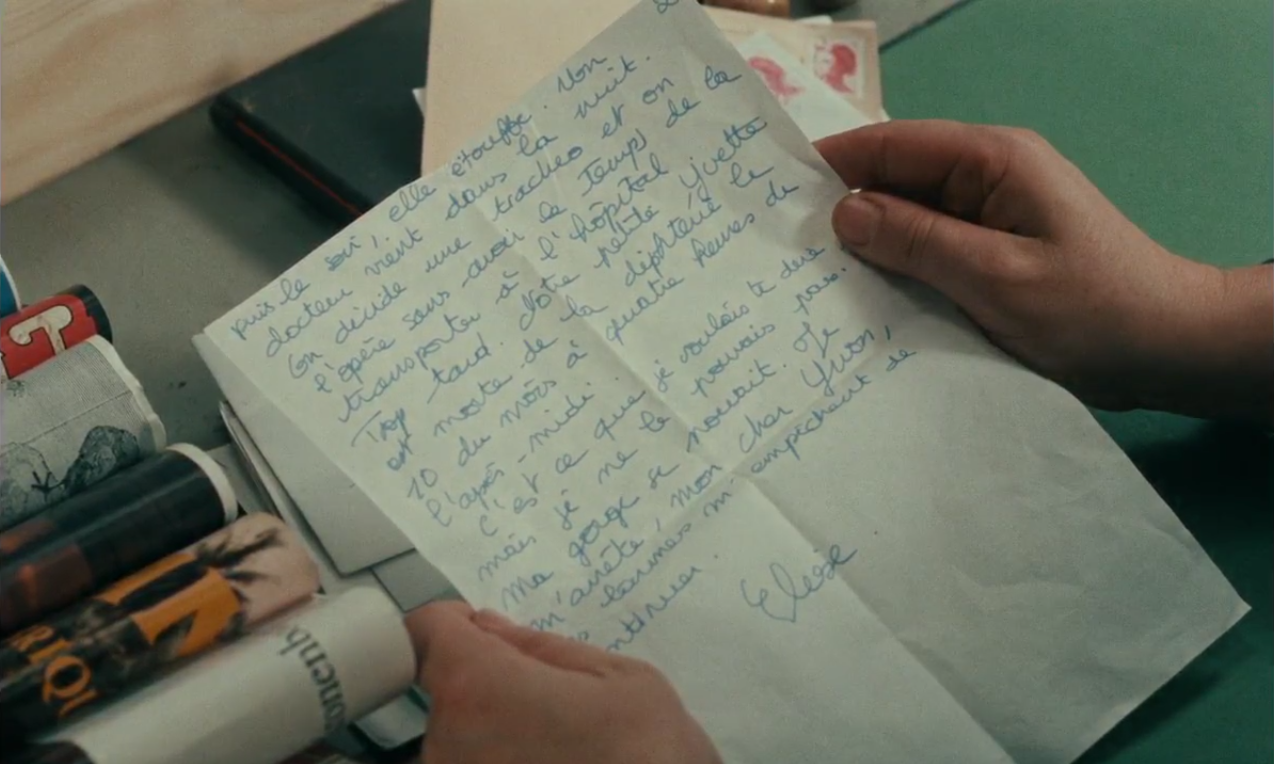

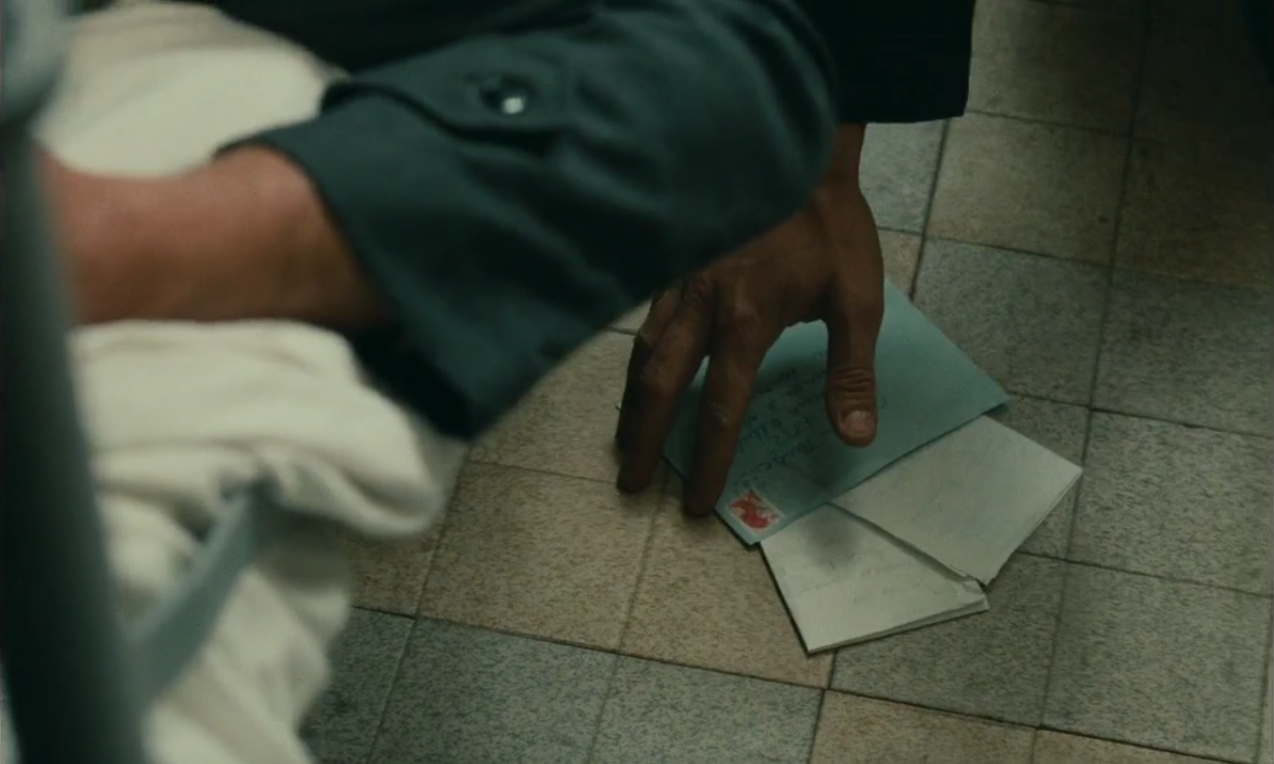

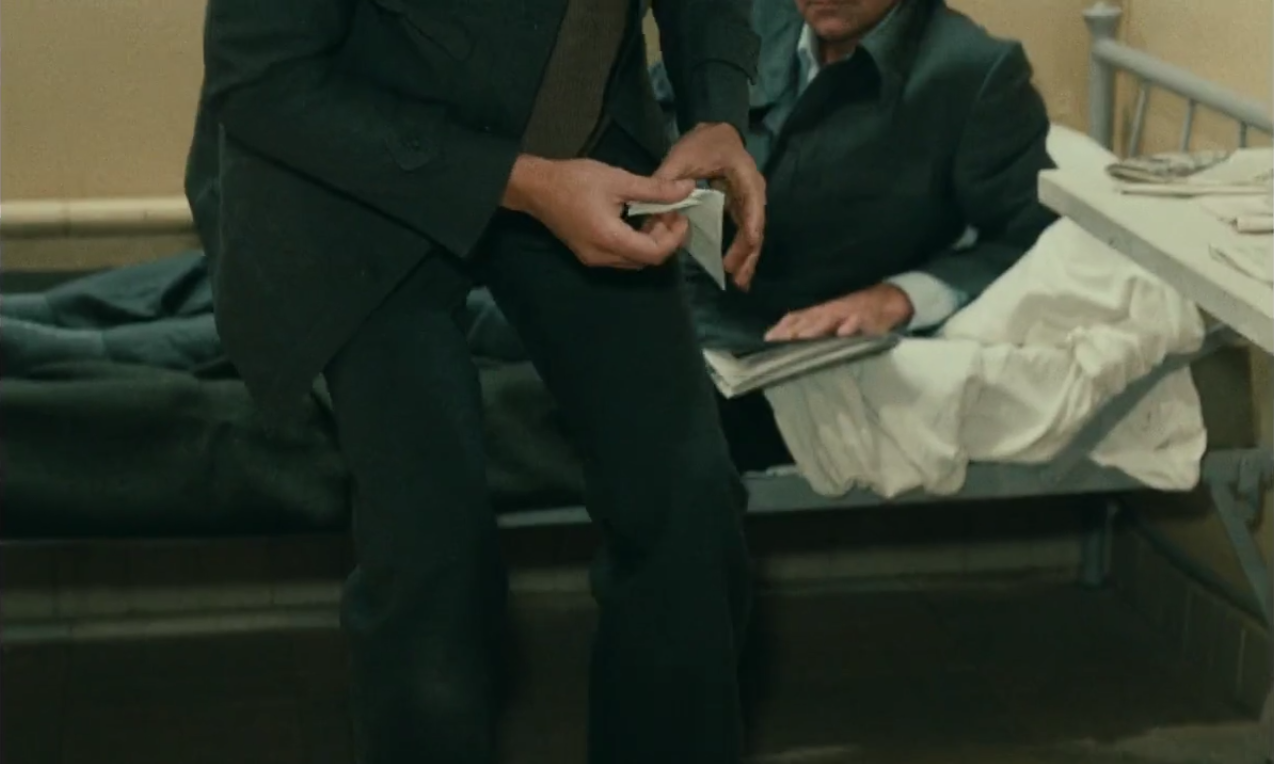

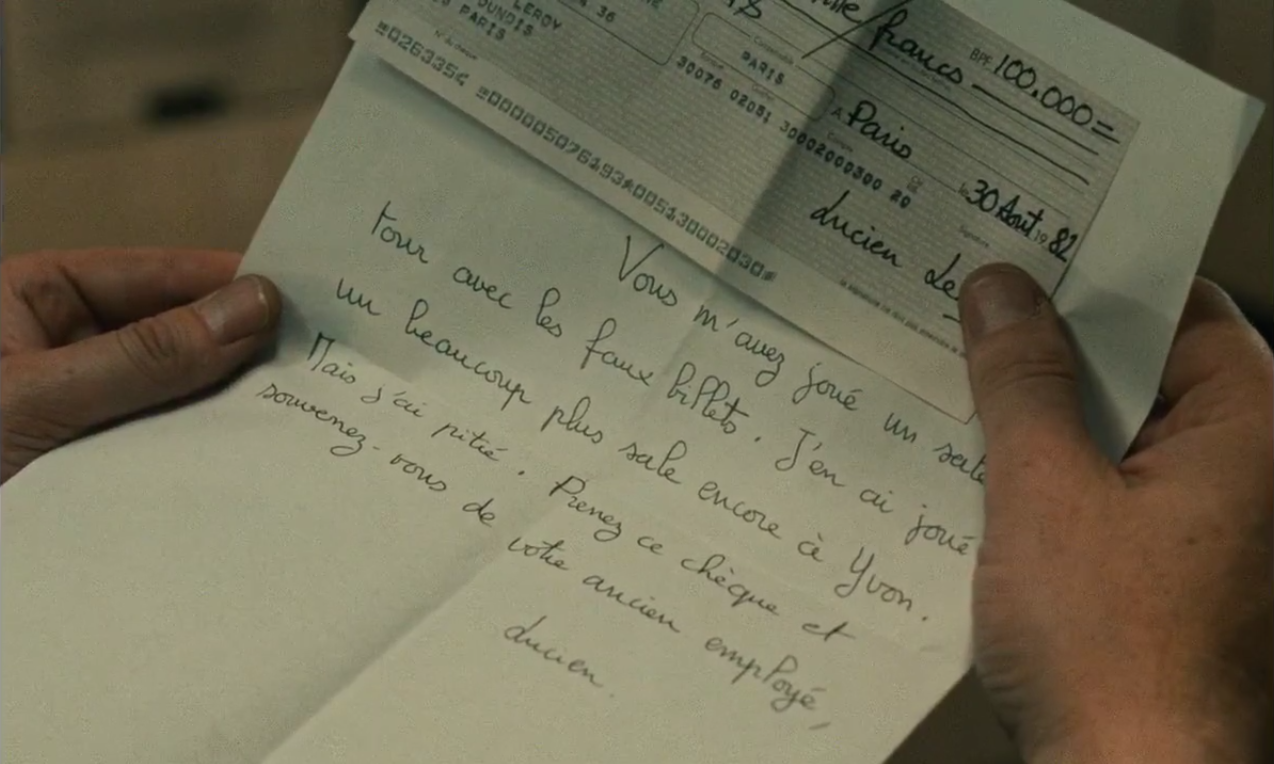

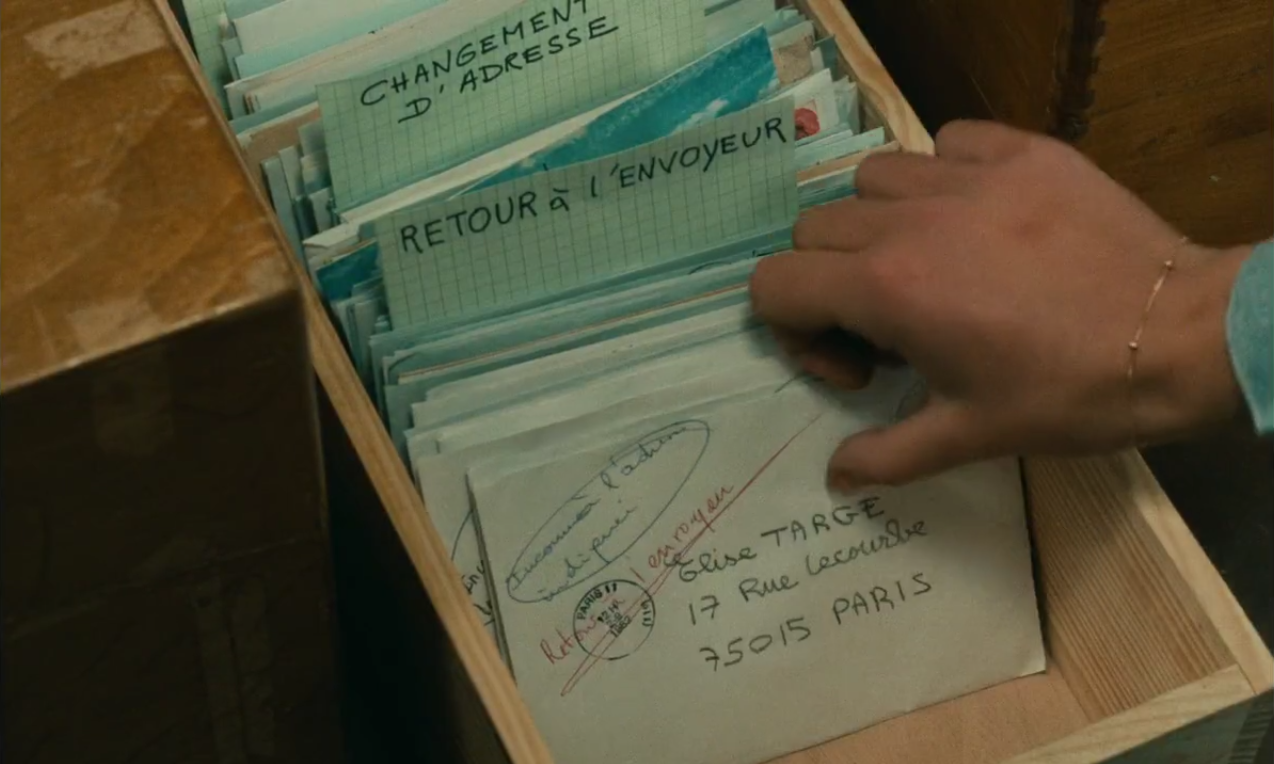

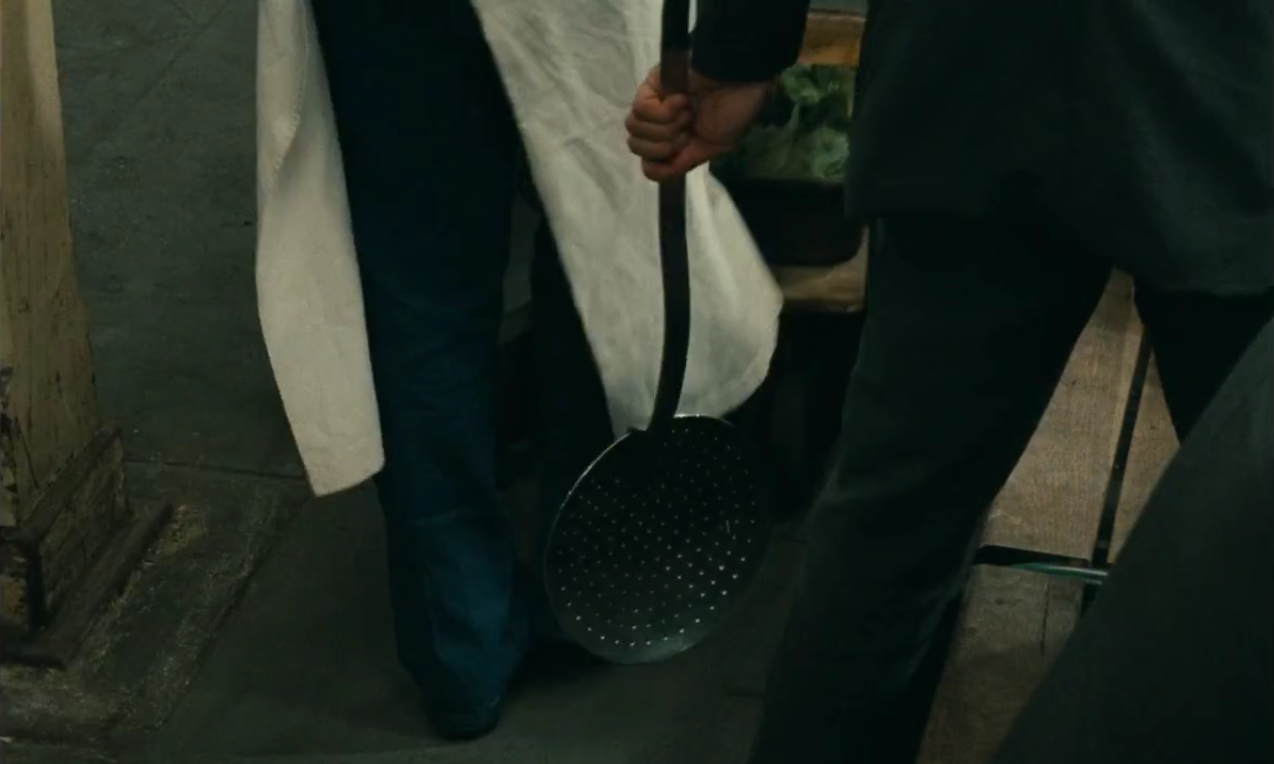

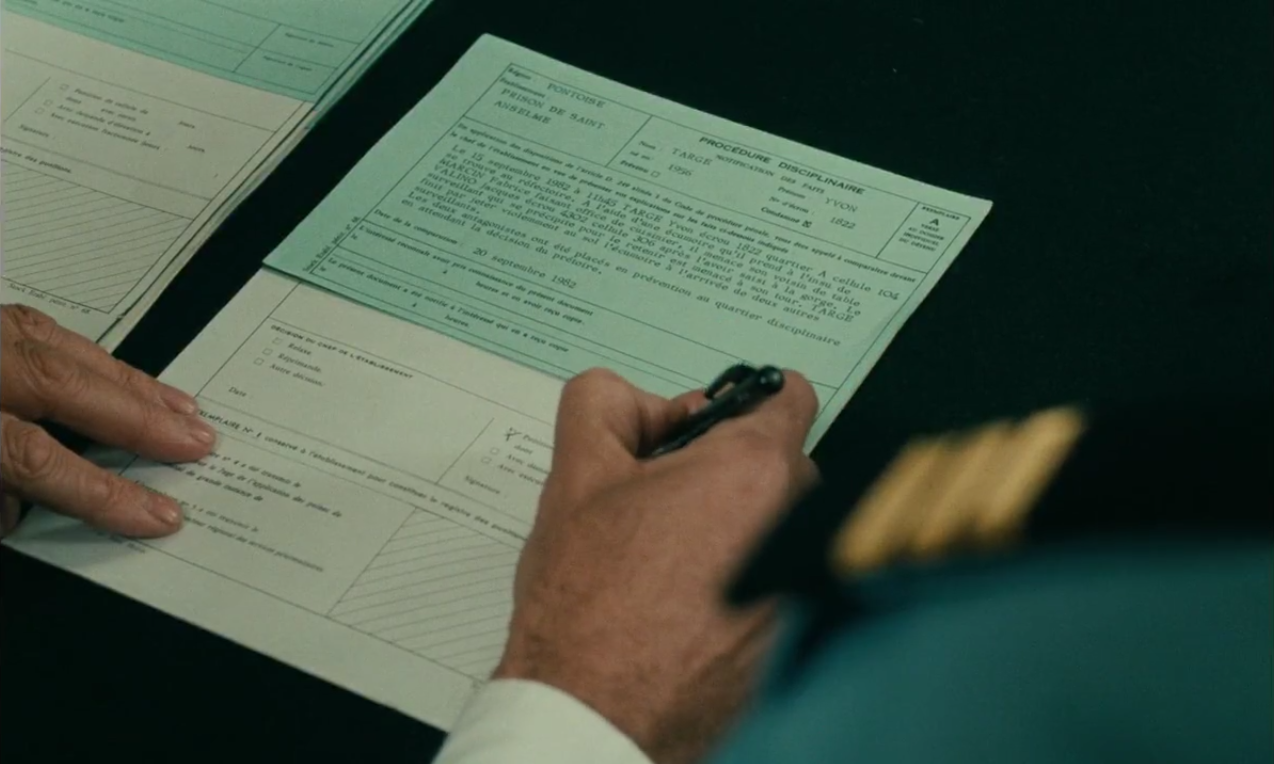

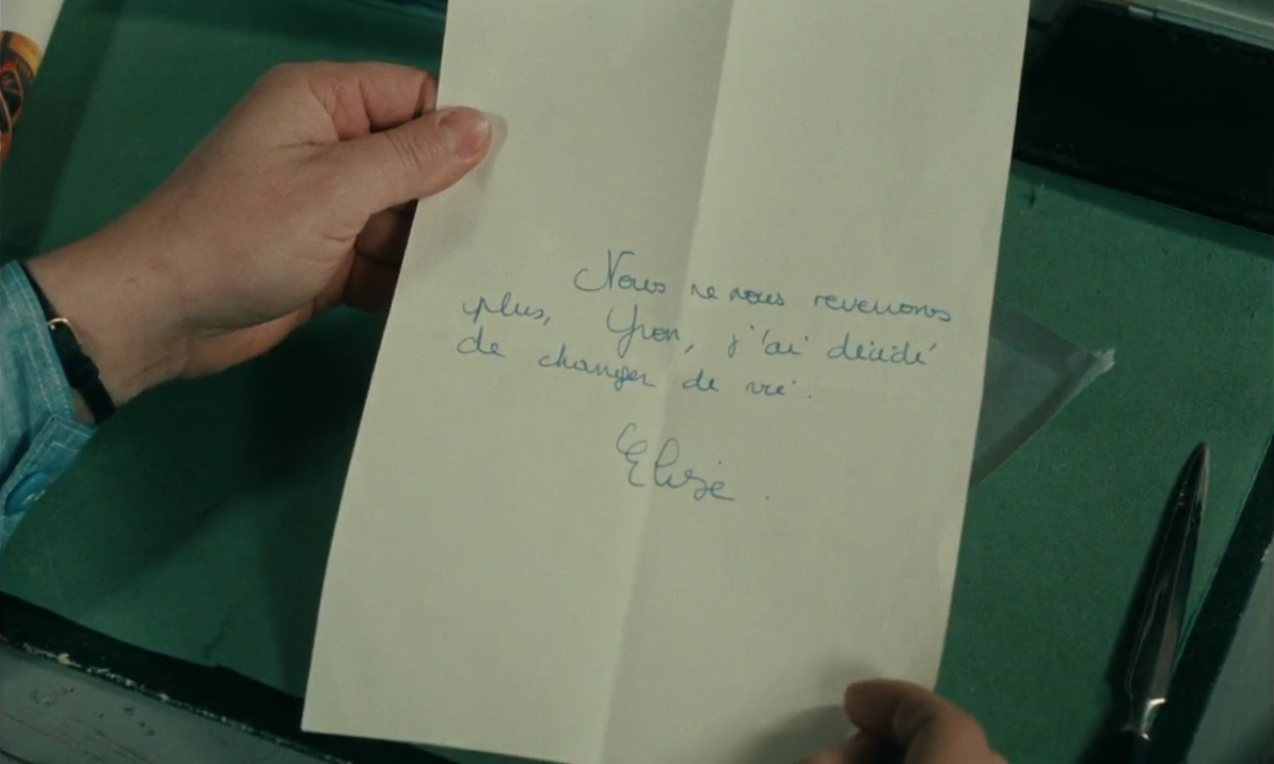

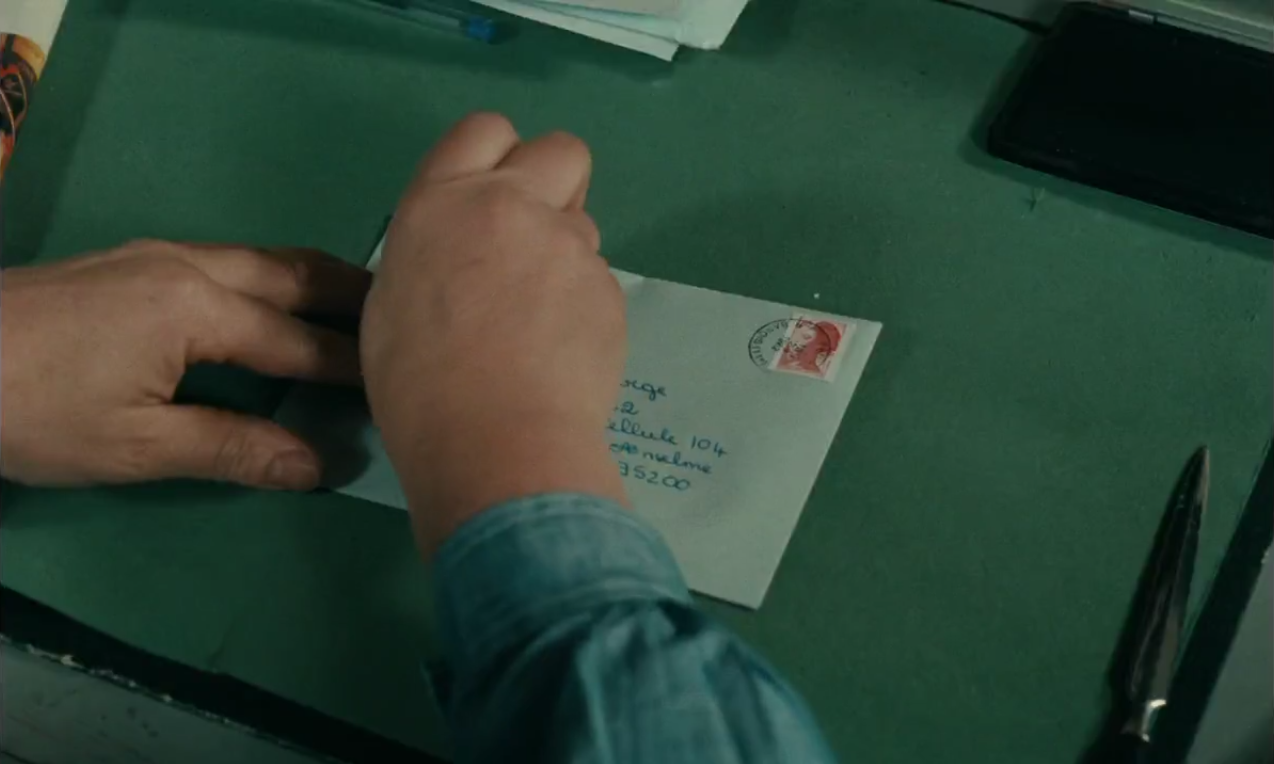

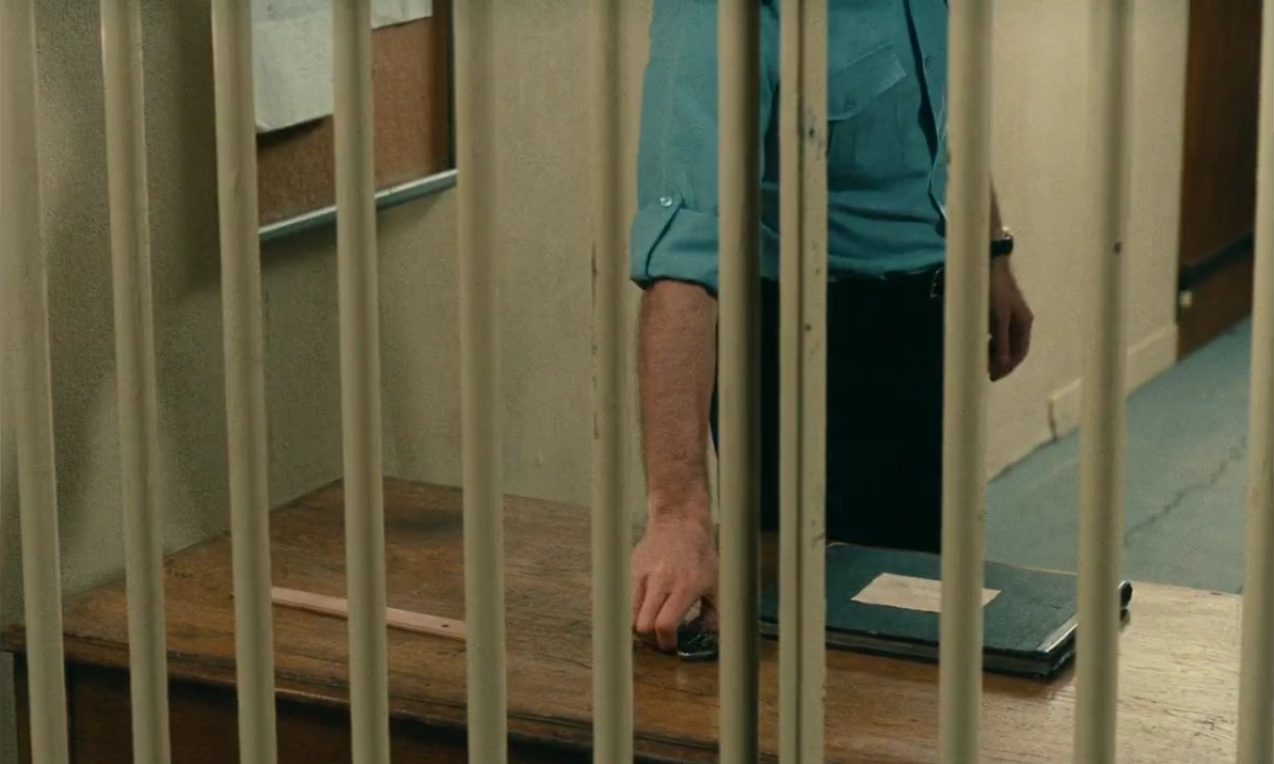

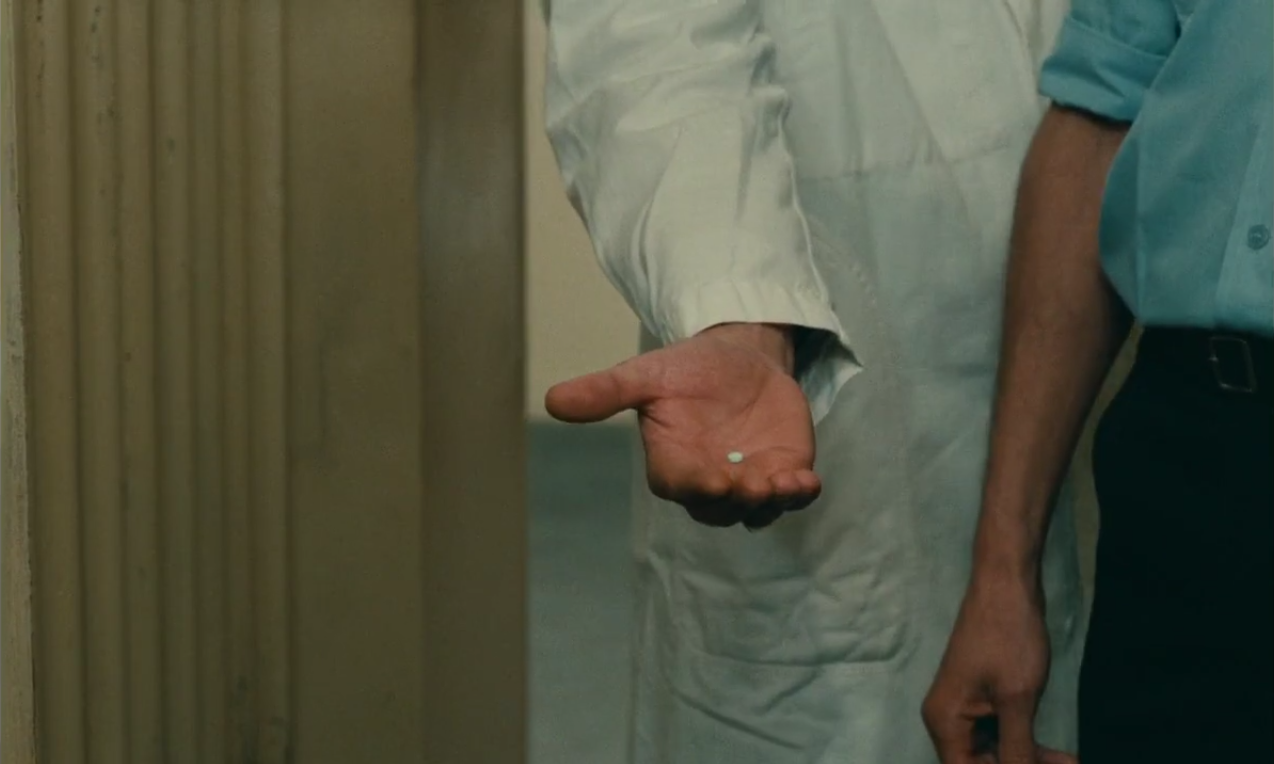

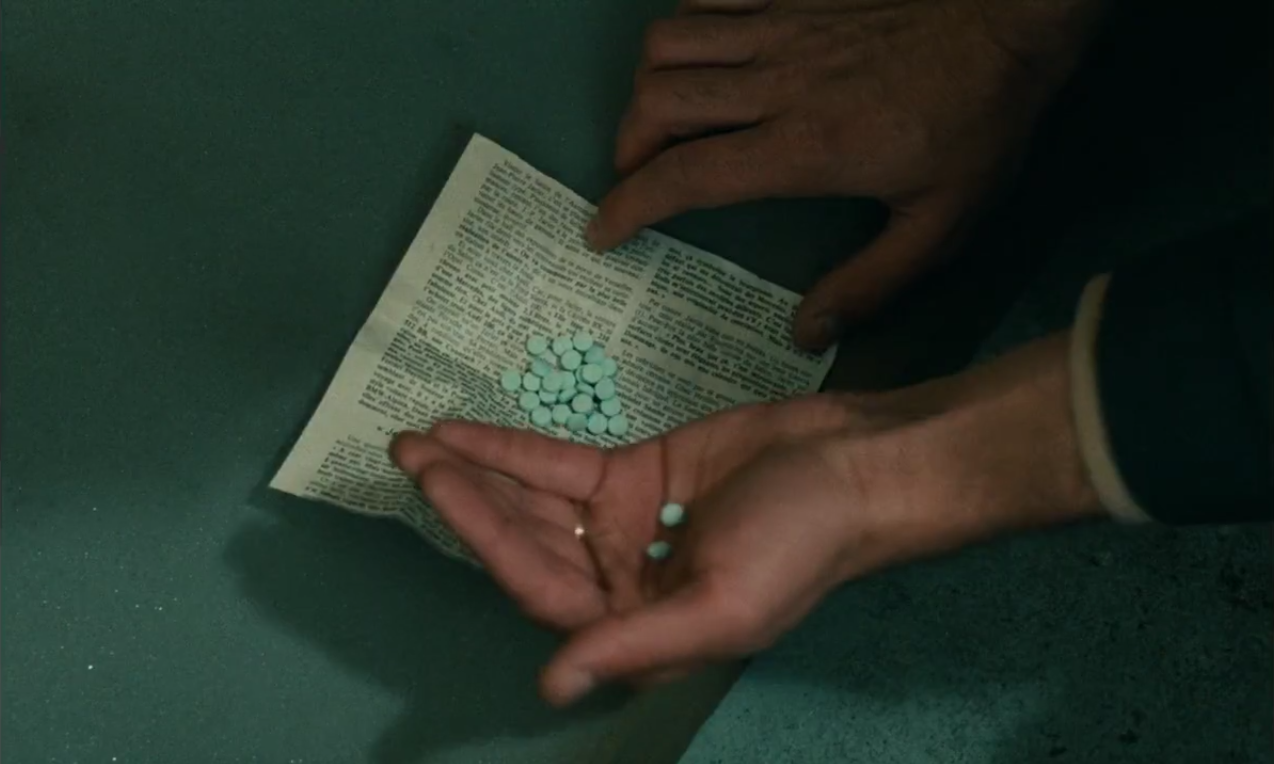

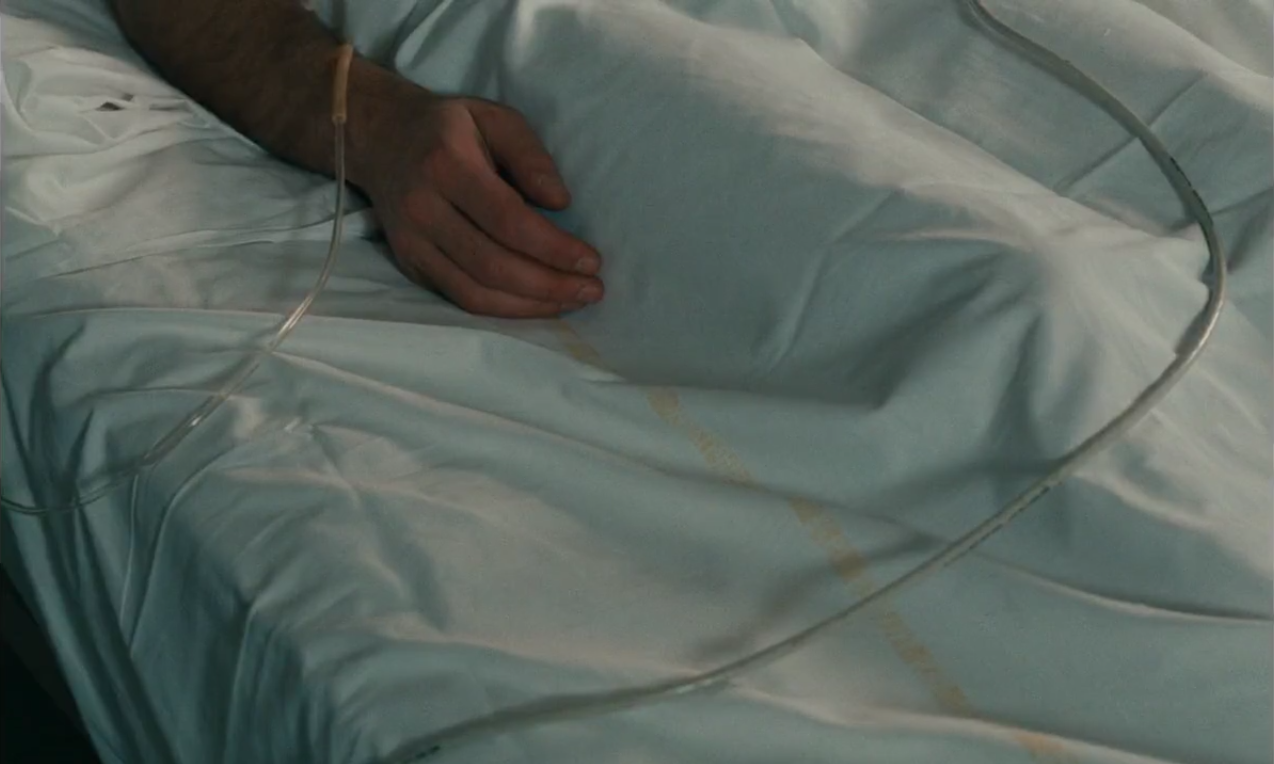

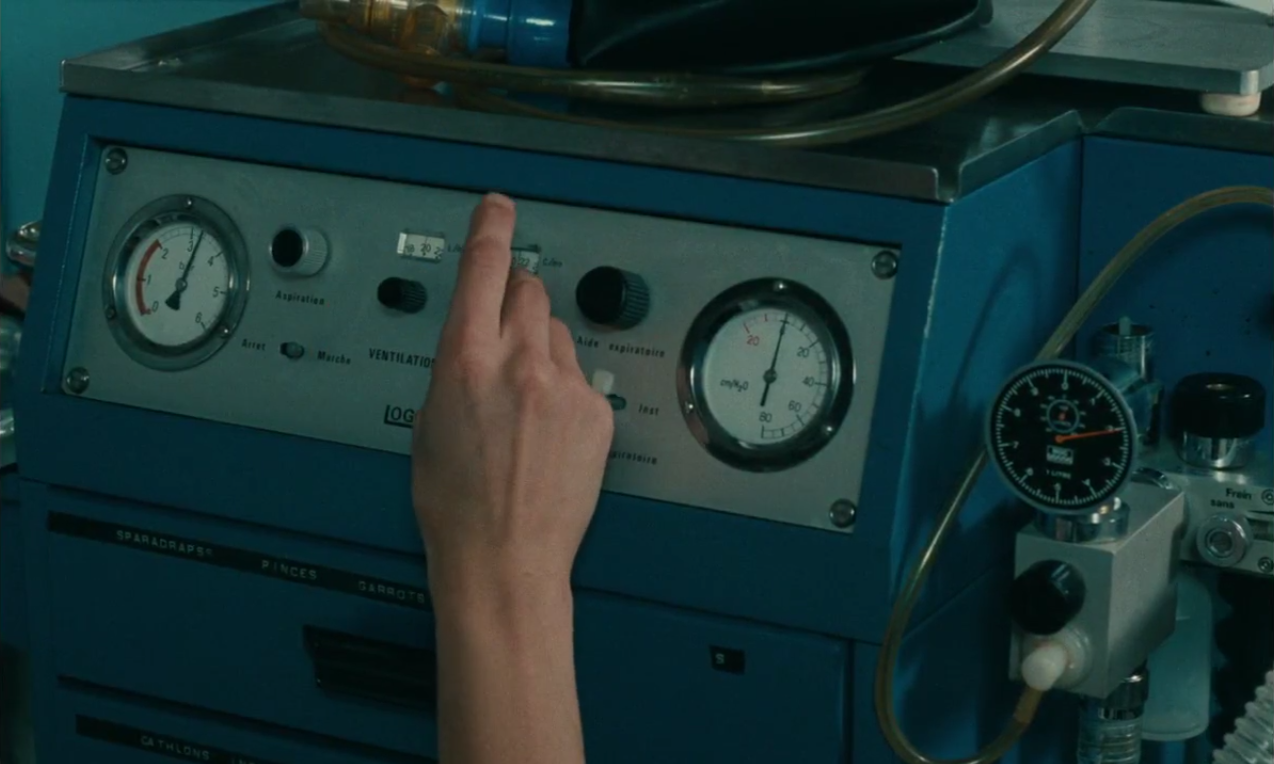

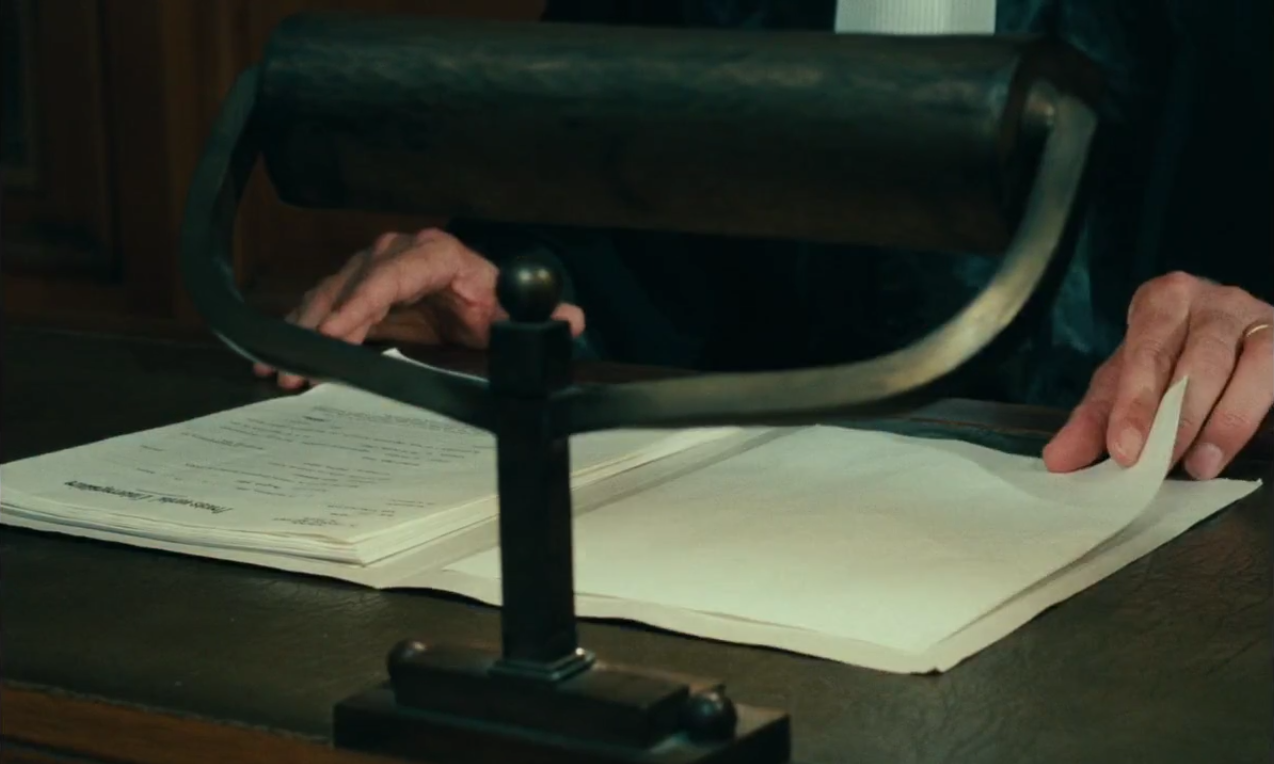

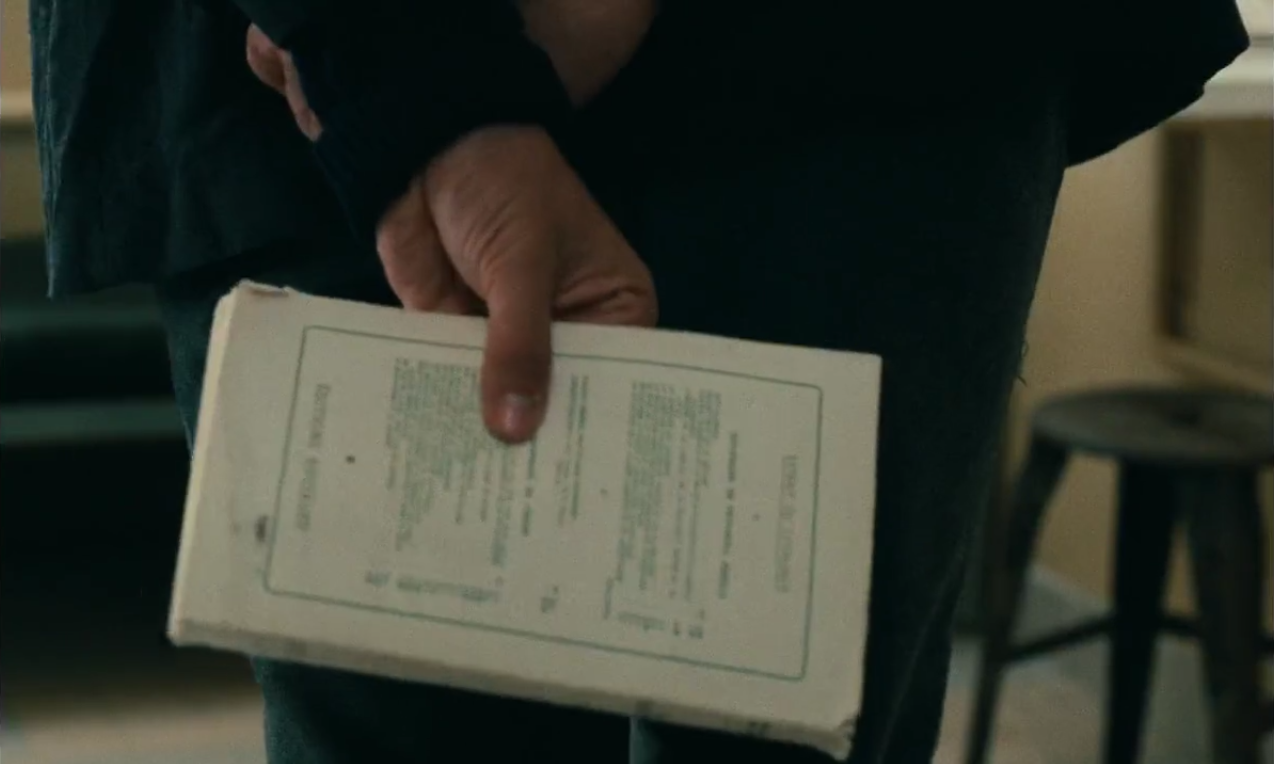

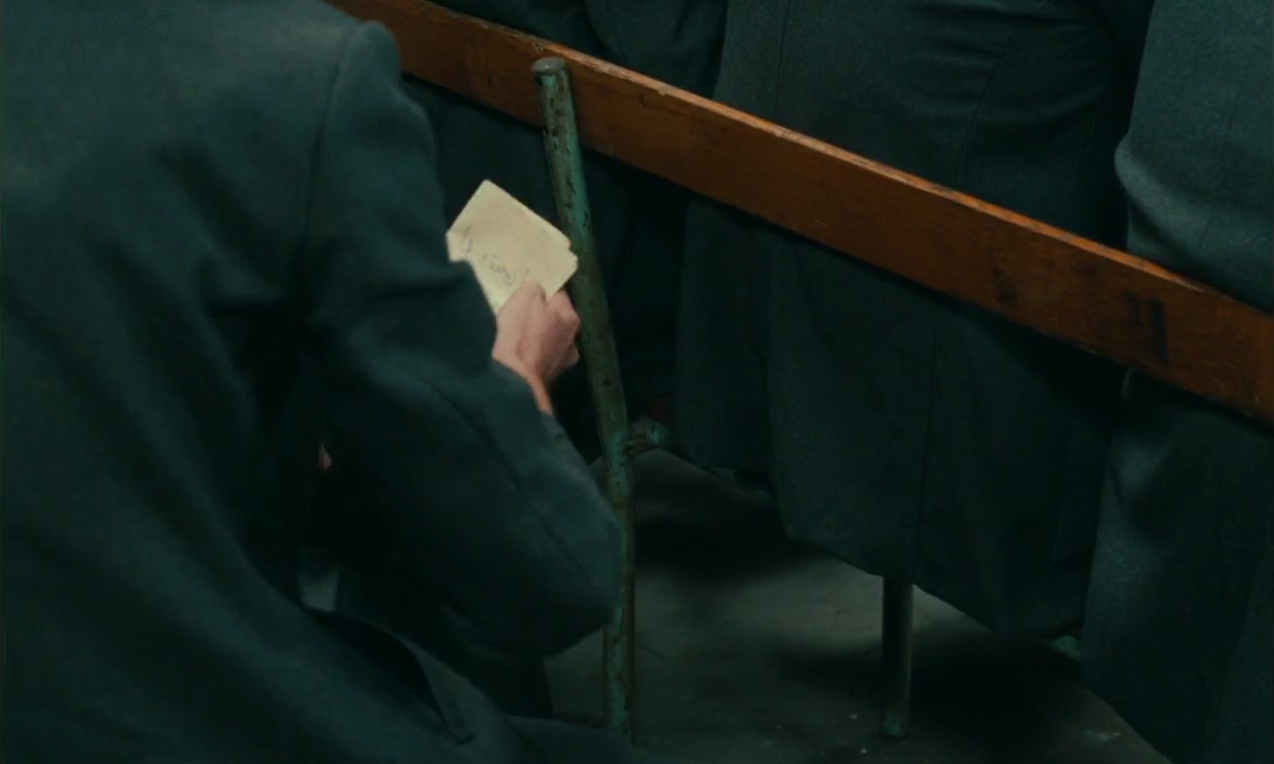

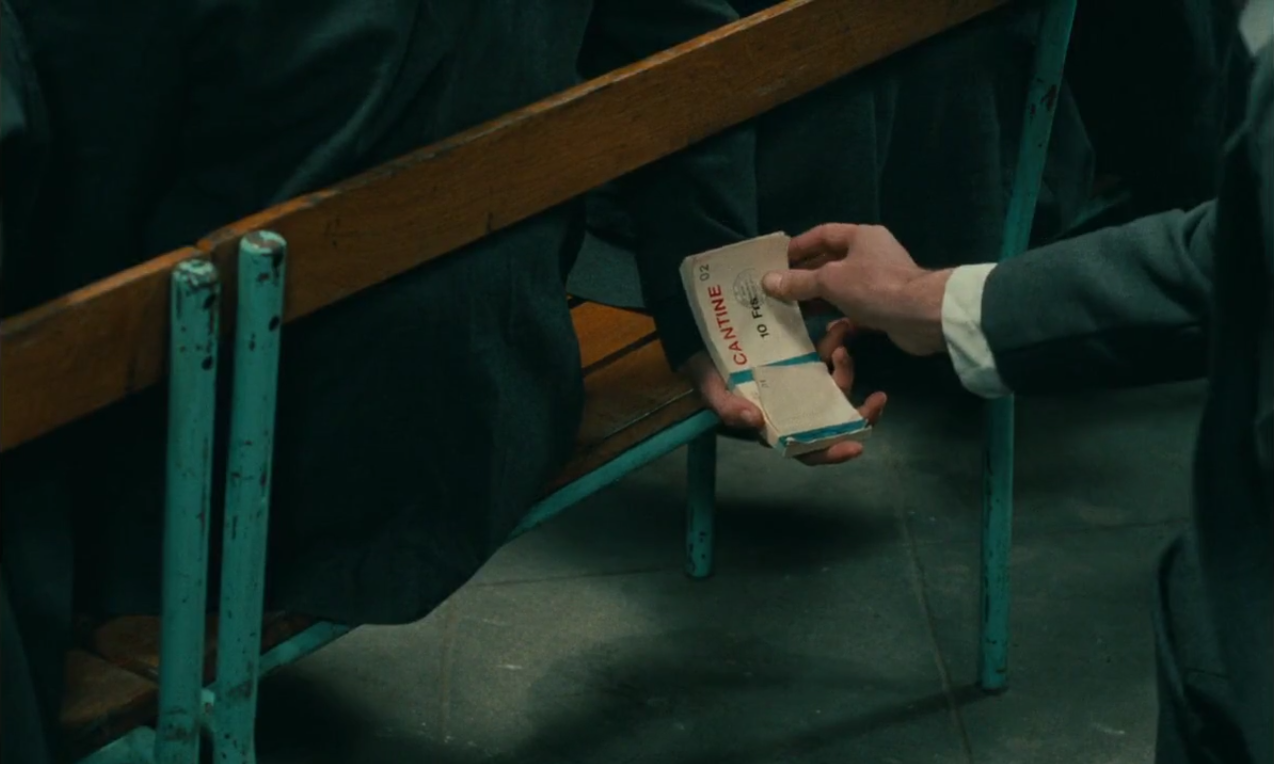

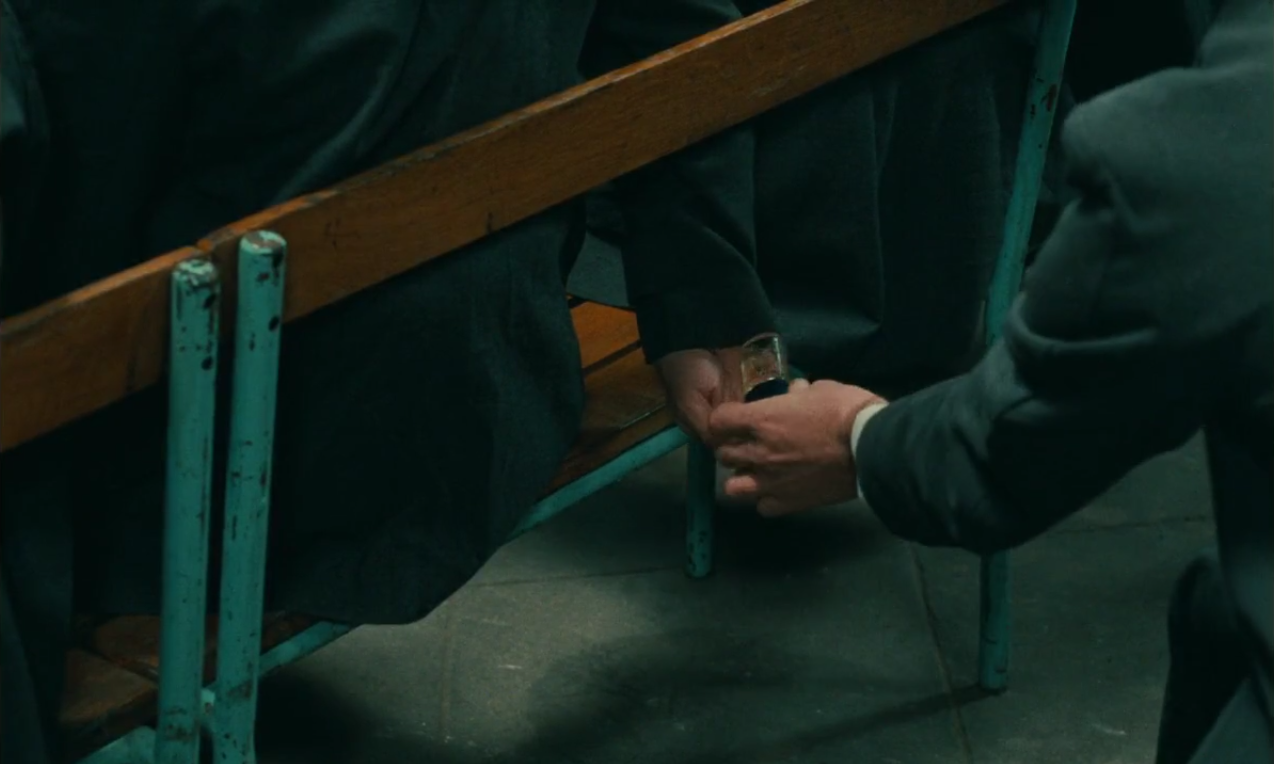

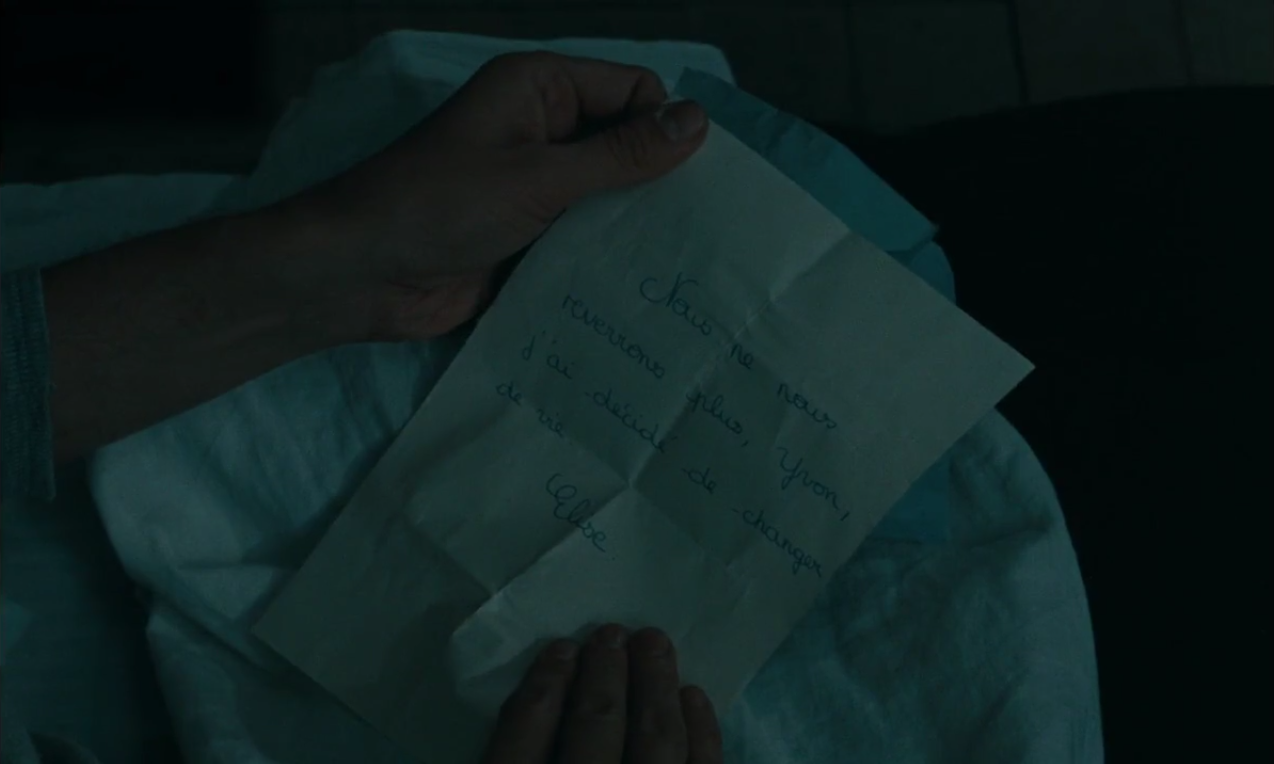

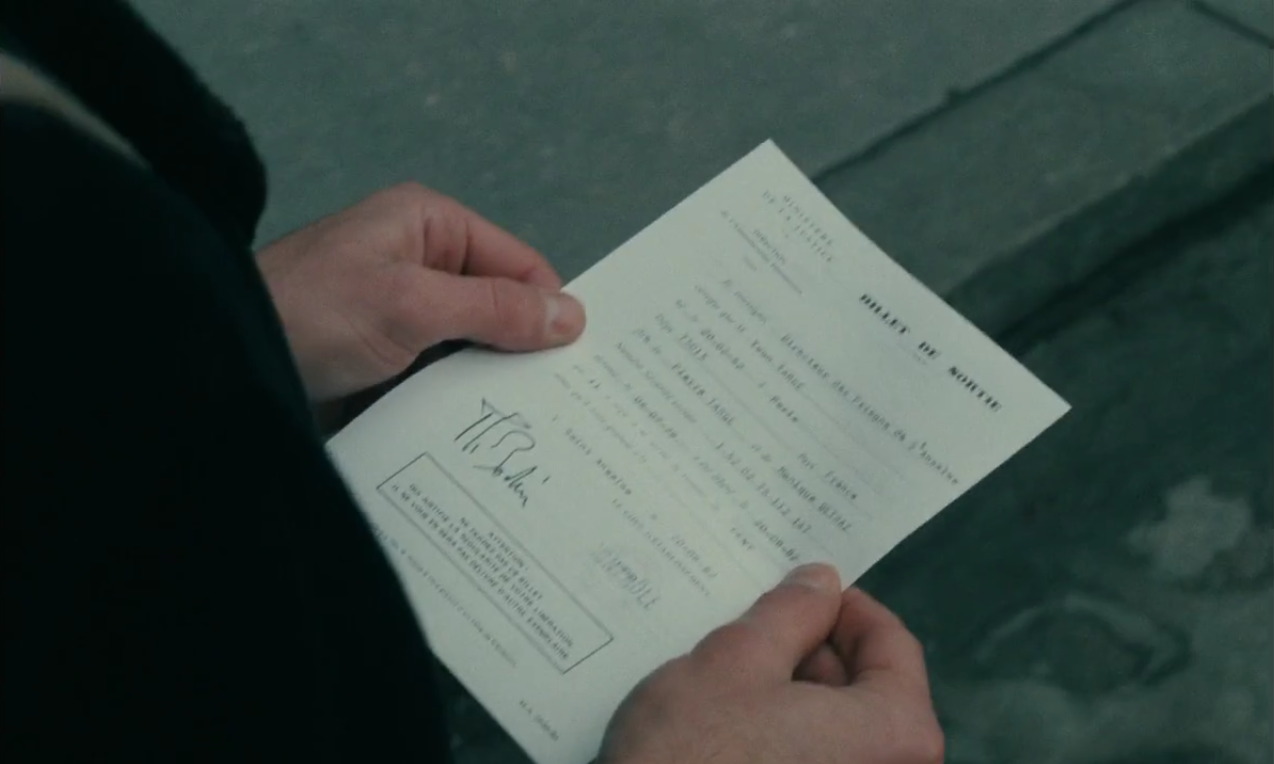

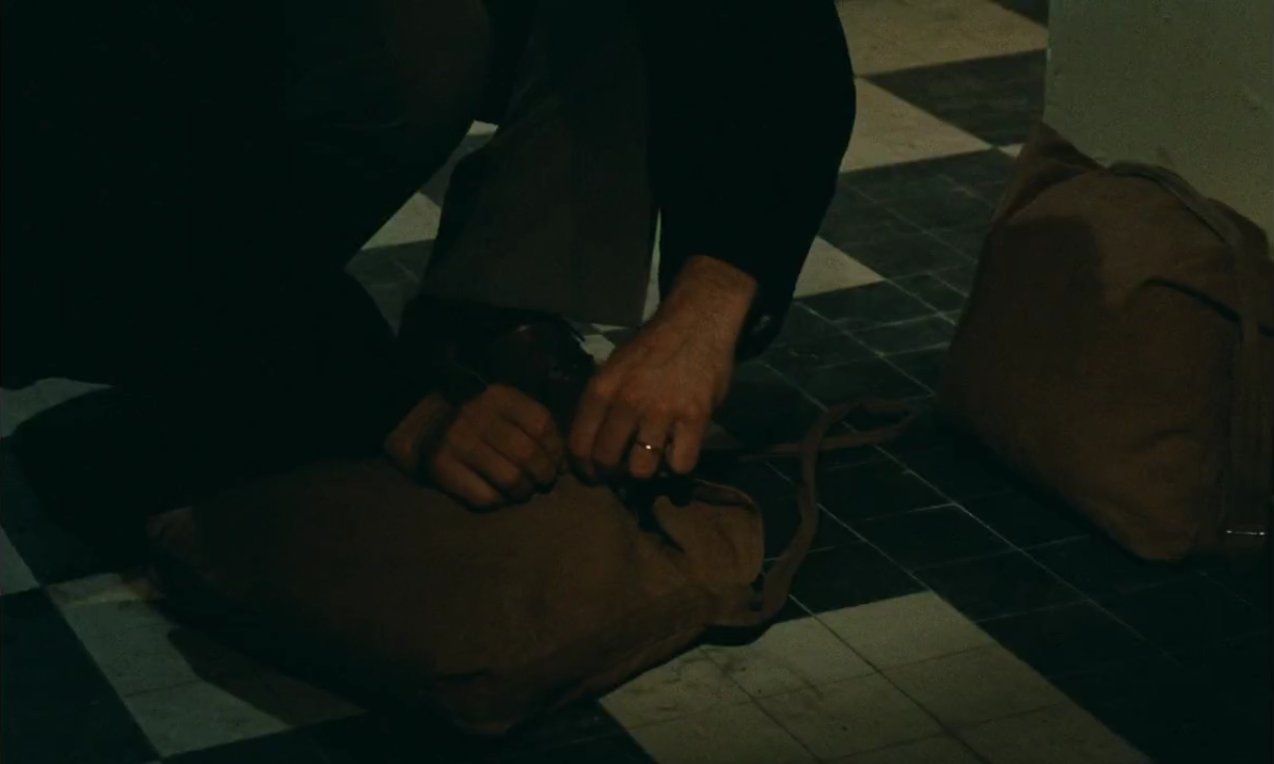

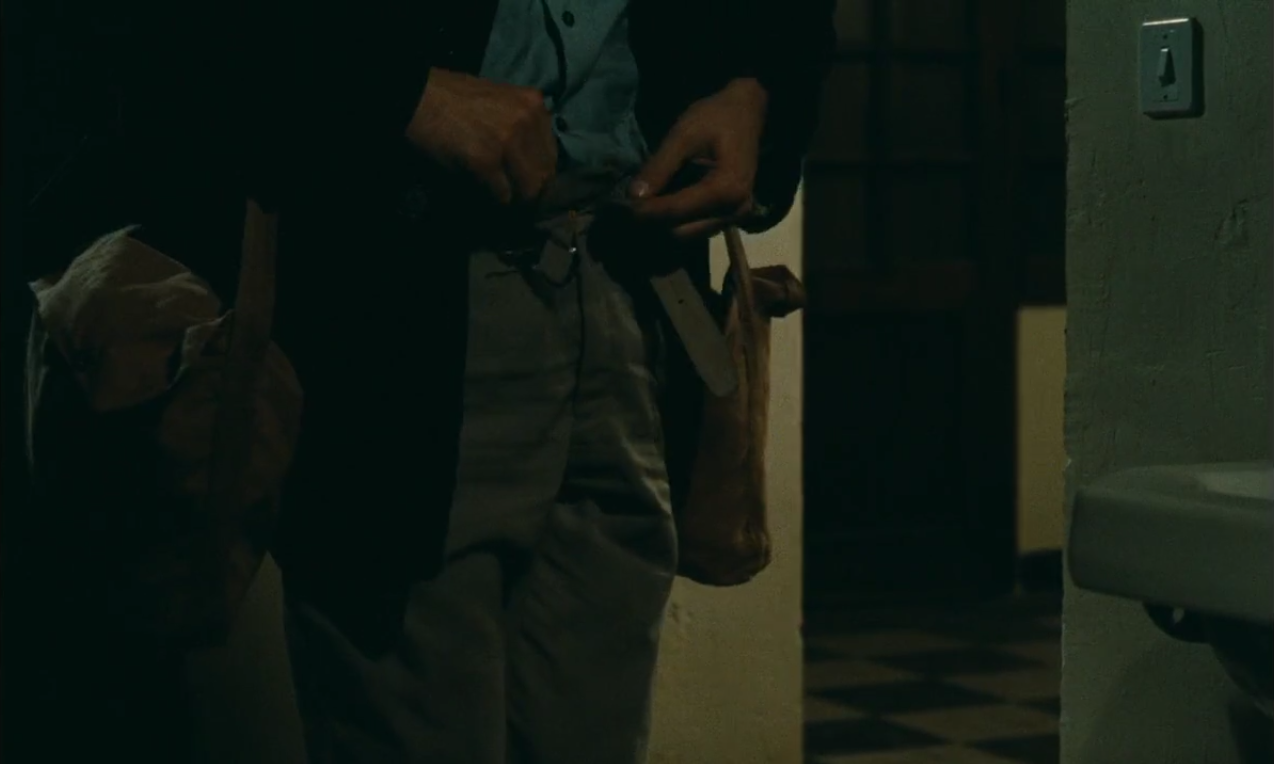

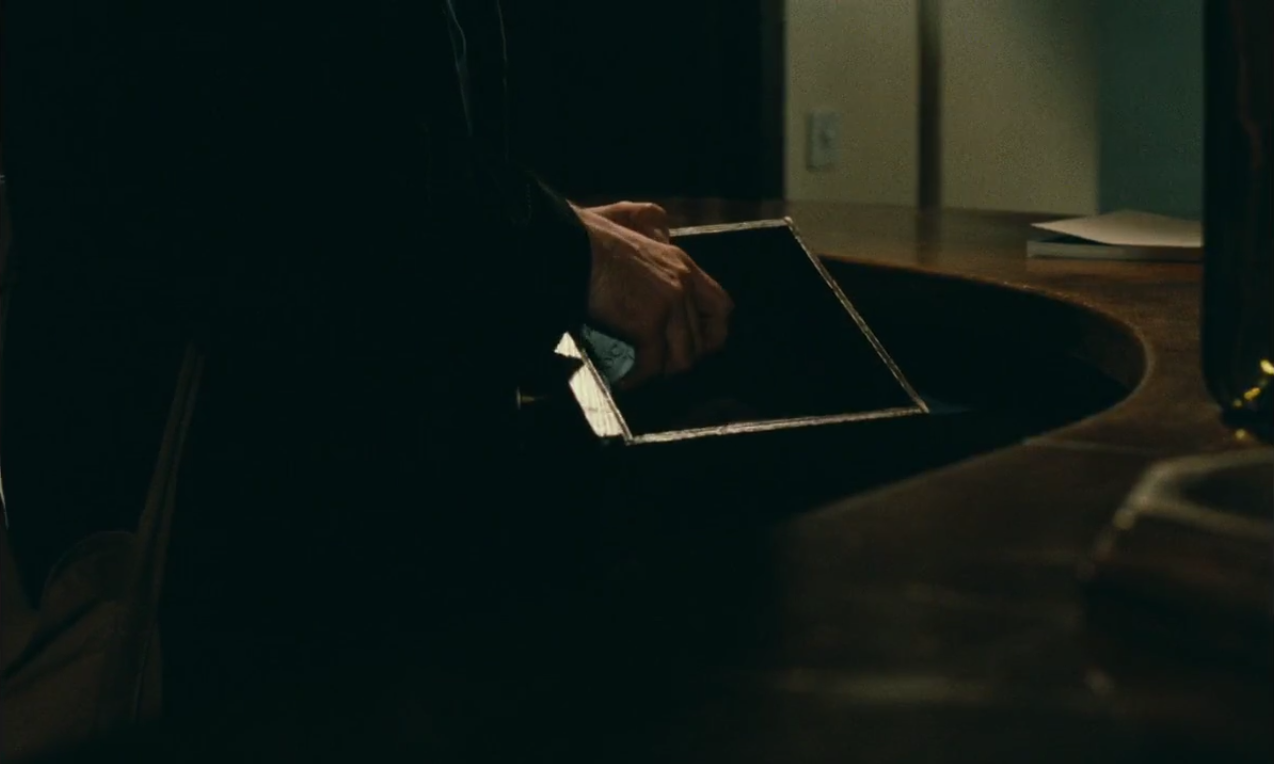

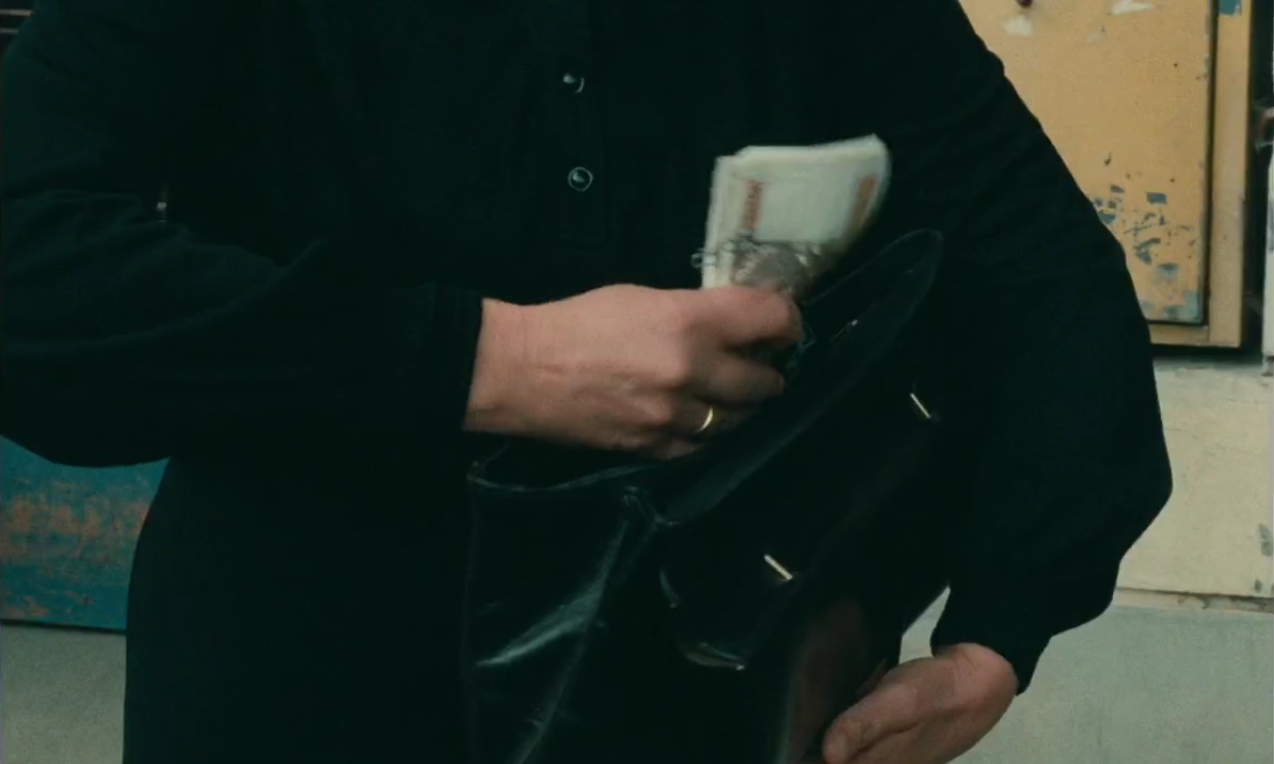

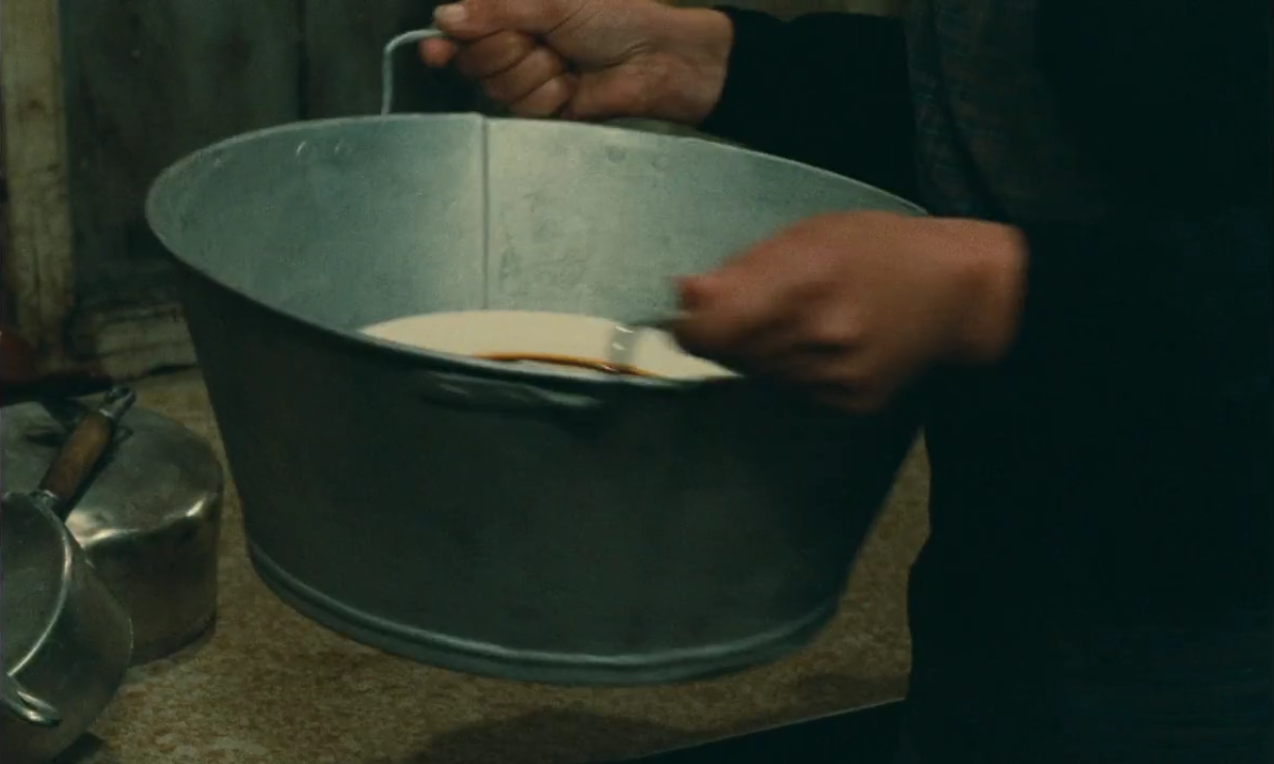

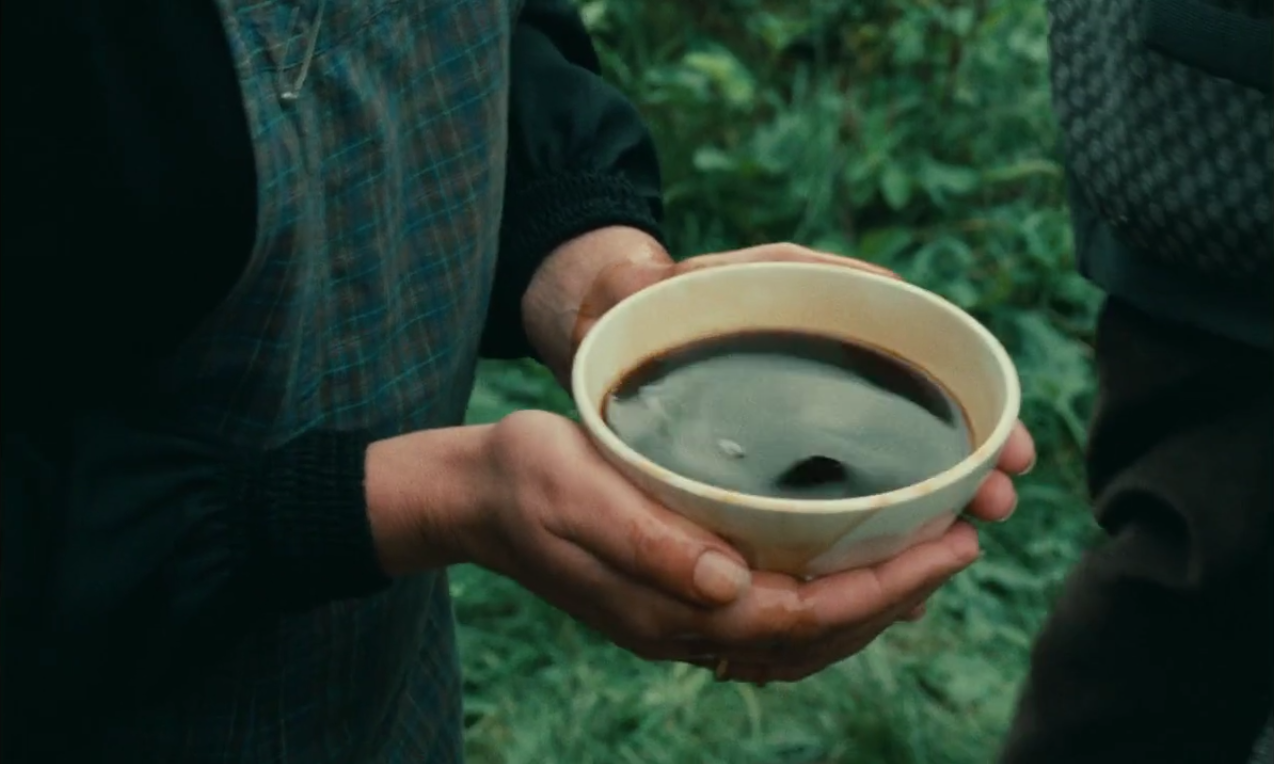

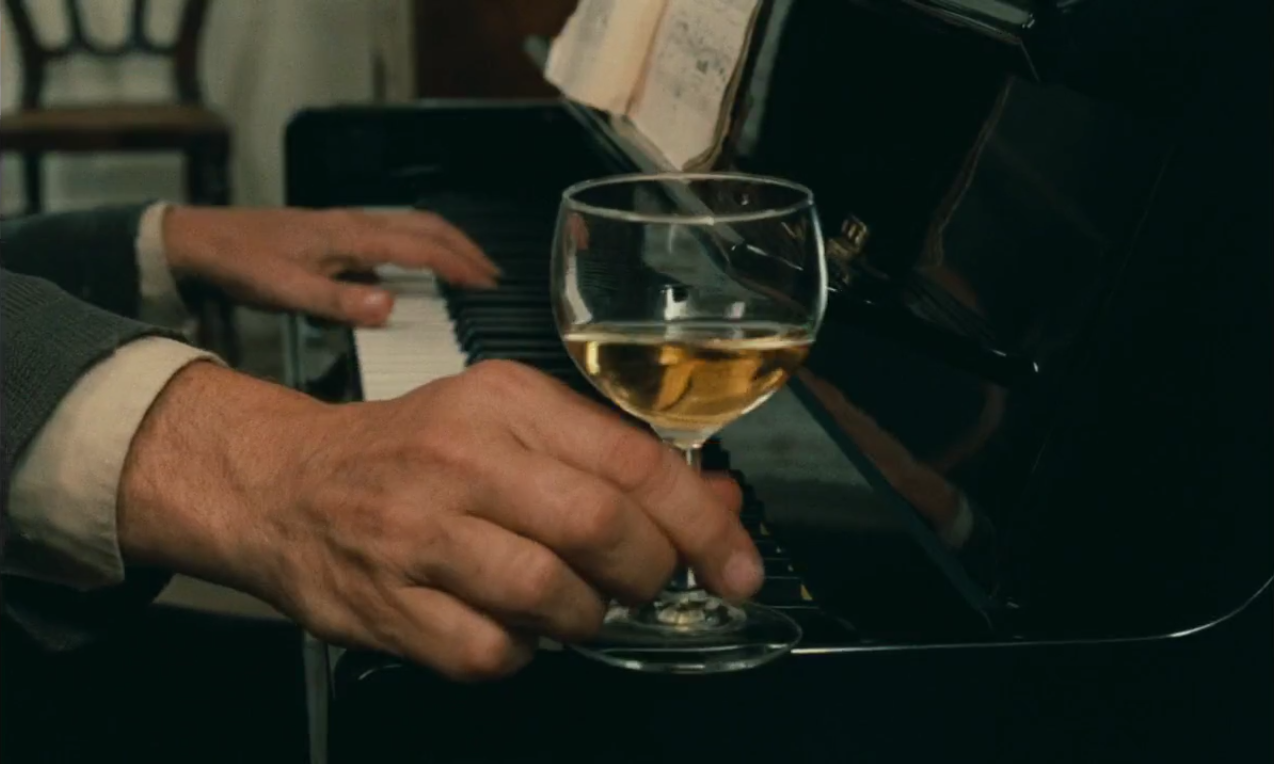

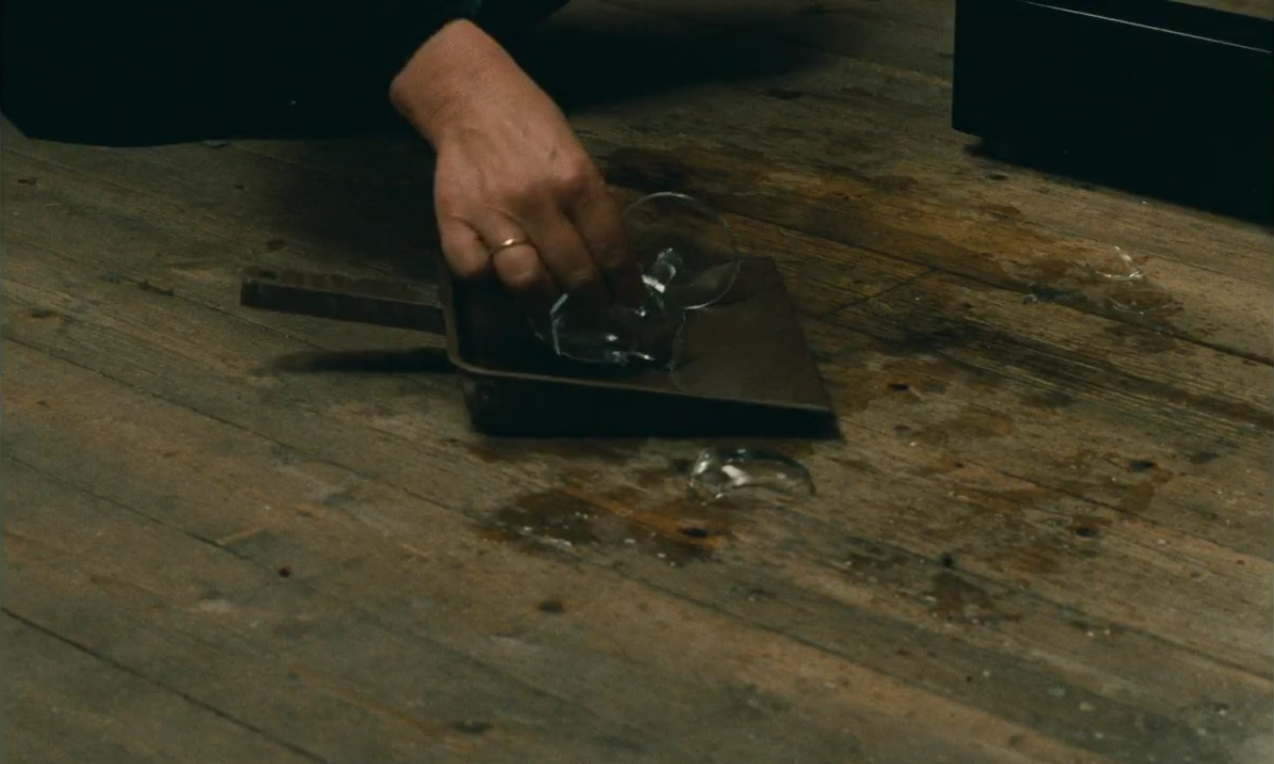

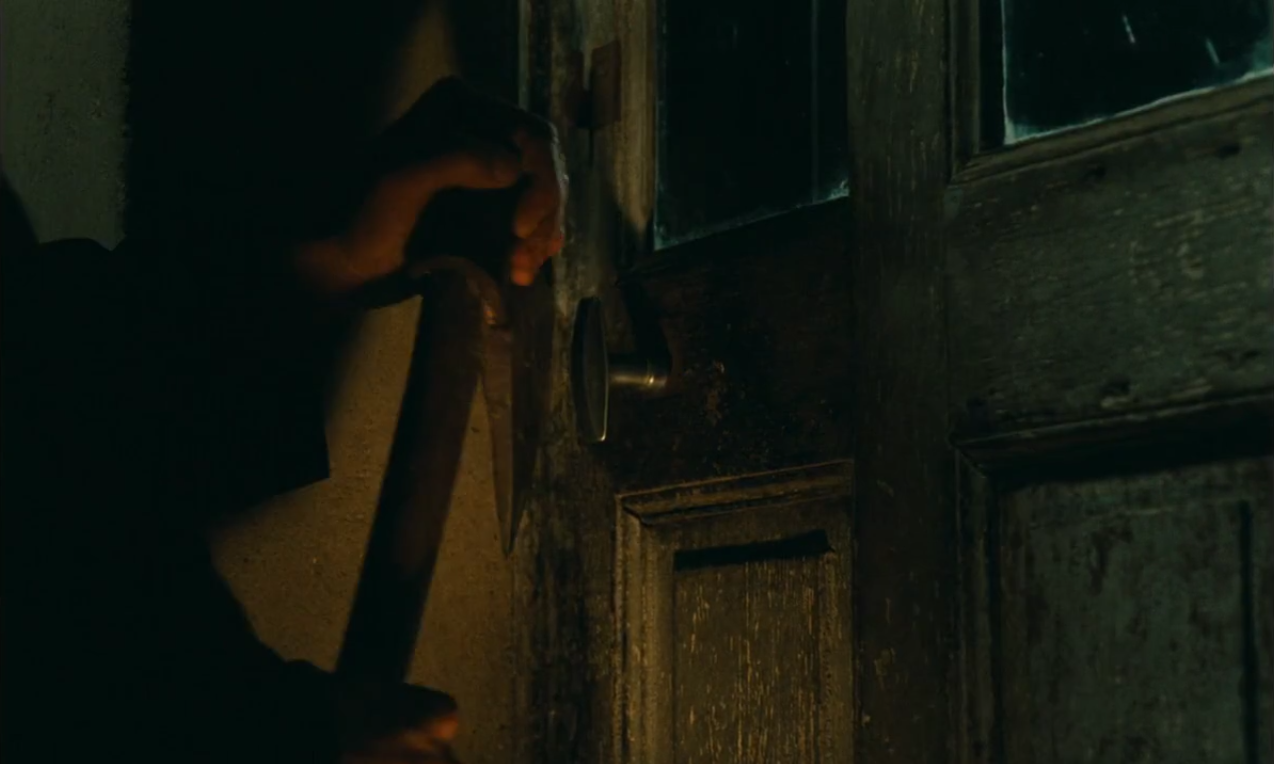

Because of these aspects and others of his unique style, many who have endured his films have denounced them as cold, unwelcoming, or simply boring. This isn't entirely wrong: an unfeeling world is a purposeful by-product of his craft and his craft is certainly not for everyone. Given my lukewarm reactions to some of his "greatest" films, I doubt that it's even for me. Yet his meticulous attention to that world is revealing, if not of the grand narrative he's smuggling beneath the cold factuality then of Bresson himself and the way he sees the world. L'Argent (1983, Money) is the final film that Bresson ever directed, and this time is passive camera settles upon repetitive close-ups of hands. The film lingers emotionlessly on shots of hands at work, hands in repose, hands grasping, exchanging, and gesturing. Bresson had previously expressed the beauty of hands-in-motion in Pickpocket (1959), but only to highlight the grace of its starring thief's dexterous digits.

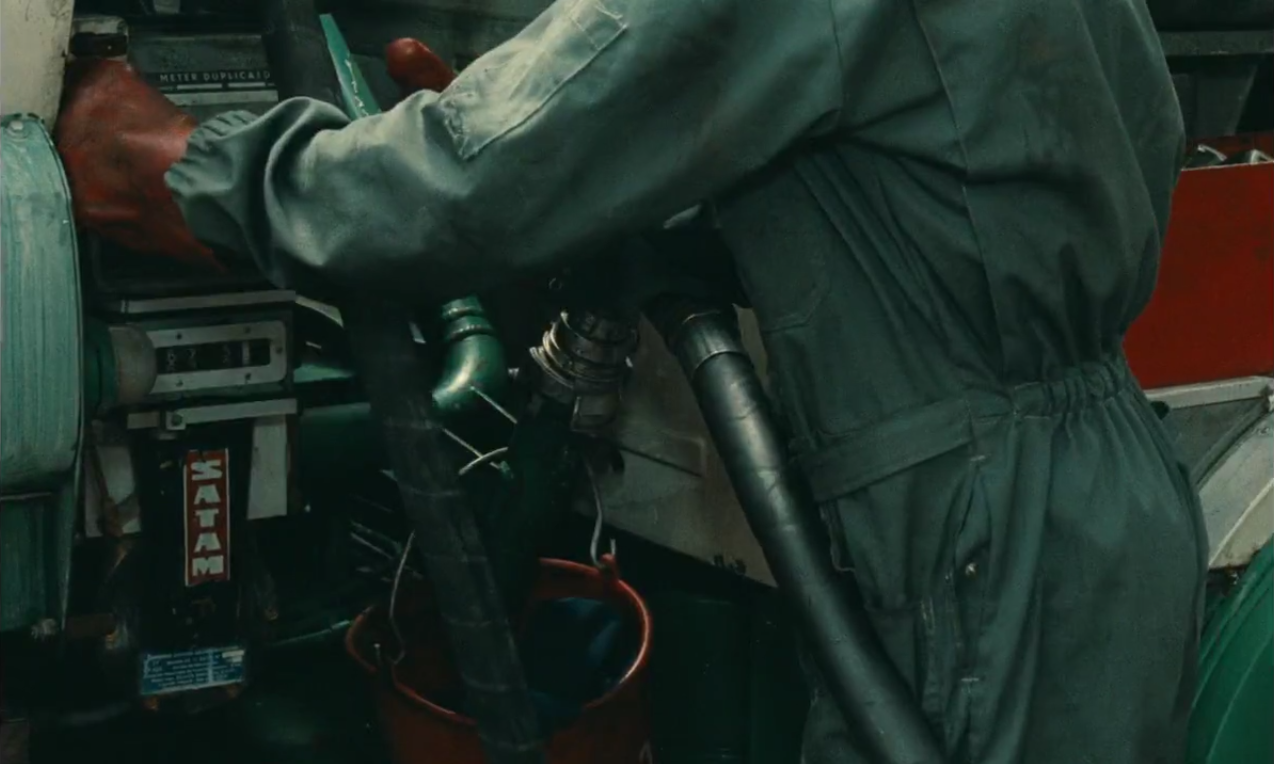

L'Argent is not concerned with special hands. Instead, it gazes upon hands as they come, as they happen to exist where it is looking. In the mundanity of the film there is something touching, something cruel, something that you can feel, and I believe that it is this fixation on hands, more than anything else, that both grounds the film and lends it its grace. While Bresson claimed to only use "necessary pictures," the grimy red color of a gas deliveryman's gloves or the elegant twiddling of hands counting bills in close-up cannot be anything but beautiful—but its only through the austere practicality of Bresson's camera-eye that we can recognize that beauty at all.

"Bresson is noted—rightly—for his parsimony and restraint, qualities rarely found in popular movies. Yet his sparse selection of images and sounds is drawn from a wide repertoire of film-making resources, and their combinations build up a complexity that may not be apparent at any given moment. It is this implicit richness of Bresson's films that embraces elements of the more familiar screen view of the world. And it is because viewers can sense this familiarity that Bresson at his best—as in L'Argent—can share with them the vivid, alien experience of his own eyes and ears."

- William Johnson, Film Quarterly vol. 37, no. 4 (1984)