HIS HUMBLE HUNCHBACK: THE STOCK CHARACTER HISTORY OF IGOR

May 13, 2019 | Essays

In the summer of 2016 I was staying with my partner at their family's house and working on my first real website: Dr. M's Frankenblog. I was just 20 years old at the time and was finally realizing, with confidence that only a 20 year-old could have, that I wanted to write. I wasn't sure if I wanted to write for a living, but I was sure that I wanted to write. Specifically, I wanted to write about movies and media (at least at the time), and so I created a gimmicky blog—imagine At the Movies by way of a television horror host—to publish my musings. It wound up being mostly reviews, but it was still a fun and rewarding project that I kept up for about six months (my return to college kicked my ass) and it was through the mysterious character of "Dr. M" that I first really experimented with tailoring my identity on the internet: a practice that would gradually lead me to reevaluating my identity in real life and coming out as transgender by the end of 2017.

This is the best piece that I ever published on the Frankenblog, a four-part exploration into that funny little hunchback character that we all know as Igor. I'm so proud of it that I'm republishing it here. It's fairly common knowledge that Dr. Frankenstein works alone in the original novel and that his lab assistant is an invention of adaptation, but what made me endlessly curious was how such a specific character archetype could congeal in pop culture when, if you really look into it, there isn't as definitive of a singular "Igor" in the history of all things Frankenstein as you may think.

Please click on the images throughout this essay for larger resolutions and more information.

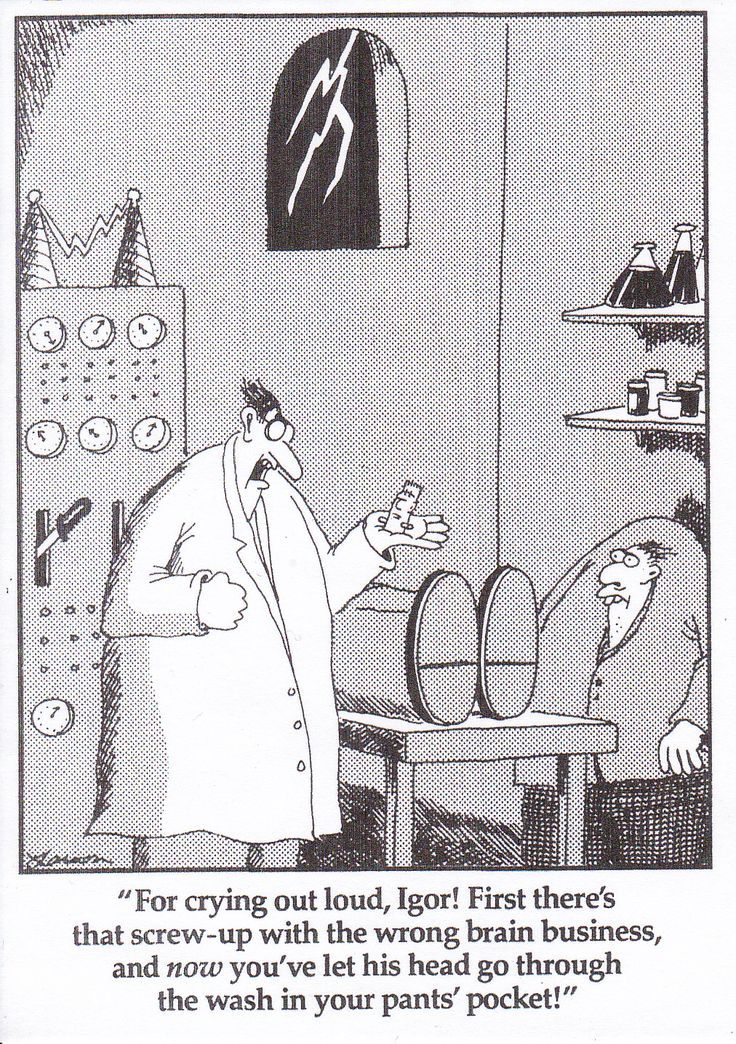

When one thinks of Frankenstein—not necessarily the book itself or any one specific adaptation, but the collective mythology—there are a few specific set pieces that spring to mind. Naturally there’s the Gothic castle and the gloomy laboratory, but one trope that seems unparalleled in its ubiquity is the presence of an "Igor," a hunchbacked assistant to the doctor. No such character ever appeared in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, but her tale of horror and hubris has been dramatized for almost two hundred years, and it has been filmed for almost a century, and various hunchbacks and lab assistants have appeared in those adaptations. Why, though, has the idea stuck? Why have hunchbacks become so endemic to Frankenstein stories? "Igor" now fits in as seamlessly as the doctor and monster into cartoons and parodies like Mary Shelley’s Frankenhole, Gary Larson’s Far Side comic, and even a Whose Line is it Anyway? sketch.

Observe in that sketch how Greg Proops immediately understands what is expected of him when he’s assigned the role of Igor. From the feral posture to the gratingly unctuous personality, the recognition of what it means to be "Igor" is instant, but Frankenstein films have had many different hunchbacked lab assistants over the years. These "Igors" are of varying loyalty (from devout to treacherous) and can possess markedly different personalities from their peers. Most curiously, there is an egregious shortage of these characters actually named "Igor." The aim of this analytical survey is to inspect how each of these different characters and their films contributed to the recognition and evolution of "Igor," to observe how these portrayals gradually coalesced into one collective archetype, and also to uncover exactly how "Igor" became the name so concretely associated with such a diverse role. As Frankenstein’s cinematic history and related media is trawled for these characters, let there be a secondary goal of finding an "Igor" that exhibits everything expected of the archetype:

1. They must be hunchbacked.

2. They must be a lab assistant and/or servant to a Dr. Frankenstein.

3. They must, of course, be named Igor.

These criteria may seem obvious, but despite the richness of Frankenstein’s cinematic history, finding an "Igor" that meets these qualifications is a monstrously difficult task.

Before we continue, some semantic clarifications: when "Igor" is written in quotes, it refers to the conceptual stock character. When the name is not written in quotes, it is being used as just that, an actual name, e.g. Fritz and Igor are both examples of an "Igor" character. Additionally, in this writing, "Dr. Frankenstein" will always refer to a character named Frankenstein, and "the monster" will always refer to some kind of monster, but "Frankenstein" itself will refer to the collective mythology, containing franchises like the Universal and Hammer series, and any other forms of media that invoke, adapt, or expand upon the story (with Frankenstein in italics always referring to something with that specific title).

As stated before, an assistant character of any kind is nowhere to be found in Mary Shelley’s novel, but other authors were far quicker to invent these characters than the mostly cinematic legacy of Frankenstein would suggest. "Igor" has roots in the numerous dramatizations of Frankenstein staged in the immediate wake of its original 1818 publication. A character named Fritz appears in Richard Brinsley Peake’s 1823 melodrama Presumption; or the Fate of Frankenstein as a stuttering simpleton at Dr. Frankenstein’s side. Presumption is the earliest known dramatization of the novel and it was followed by a swarm of imitators; from musical comedies to terrible dramas, adaptations of Frankenstein were very much in vogue in the nineteenth century. Each adaptation added original characters and trimmed excess from the book to make the plot more palatable for theatergoing audiences, and it’s not hard to see why when one remembers that the book is mostly comprised of brooding ruminations. Some other adaptations included assistants by other names (like Strutt, from Thomas Hailes Lacy’s 1867 Frankenstein: or, The Man and the Monster) but to my knowledge, none of them were necessarily hunchbacks nor were any named Igor. Whether an "Igor" or not, giving Dr. Frankenstein an assistant—especially one like Peake’s Fritz—was the easiest way to not only give the doctor someone to talk to, but to also provide comic relief and exposition in an otherwise grim and mysterious story.

Frankenstein plays continued to be produced as the twentieth century came, but the book was soon adapted for the fledgling film industry at the same rabid rate. Three Frankenstein films were made in the silent age of cinema, one each in 1910, 1915, and 1920, but only the earliest has survived; the other two are considered lost films. As far as the record shows, none of these early films contained an "Igor" and all portrayed Dr. Frankenstein as working alone (making them more faithful than the stage adaptations). When the industry embraced sound, Universal Studios turned towards the existing abundance of Frankenstein plays for one suitable to adapt to film. Although heavily revised by studio screenwriter John L. Balderston, it was eventually Peggy Webling’s 1927 play Frankenstein: An Adventure in the Macabre that was acquired, and in 1931, directed by James Whale as Universal’s iconic feature Frankenstein.

The 1931 Frankenstein has, of course, been one of the most impactful films in the history of pop culture. Few who know of Frankenstein don't immediately picture Boris Karloff with bolts in his head before they remember any other actor's turn in the role, let alone any particular line from the novel. It's responsible for popularizing a number of aspects of Frankenstein that differ from the novel, such as the creature's muteness, but most relevant to our present endeavor is its casting of Dwight Frye as Fritz, the hunchbacked crony of the film's Dr. Frankenstein. Frye’s character bears some similarity to Fritz from Peake’s Presumption (then a more than a century old) to the extent they're both bumbling, jumpy fools in subservient roles. However, the Fritz of the film is much crueler than Peake’s and is much less central of a character. This Fritz doesn’t have any comic monologues; his dialogue is relegated to scant yelps and complaints made while hovering around the doctor. Of extreme note here is Fritz’s biggest contribution to the plot, his bungled acquisition of an "abnormal brain" for the monster—given that Dr. Frankenstein was actively searching for only the most optimal parts, such a mix-up would never have occurred under his conscious watch. The inclusion of an assistant character for Dr. Frankenstein was deemed necessary by the film's writers because without Fritz’s error and consequential lie of omission, that brain never would have gone into that body. Fritz’s second-biggest contribution is breaking the seal on the film’s body count, hanged by his own whip, which catalyzes Dr. Frankenstein’s decision to destroy his creation. That’s another thing about "Igor" characters: more often than not, they're perfectly expendable.

Frye's performance as Fritz may have been part of a landmark pop cultural achievement, but he was more than a one-note lackey. Frye was a prolific character actor throughout the 1930s horror boom and his other roles may have contributed to the "Igor" archetype through sheer association. He appeared in the sequel to the 1931 film, Bride of Frankenstein in 1935, as a grave robber named Karl hired by Dr. Frankenstein's unscrupulous new partner Dr. Pretorius. This film was also scripted by Balderston and directed by Whale, and while Karl is in a similarly subservient role to Fritz, he lacks a hunchback or any kind of noticeable deformity. He's also one half of a whole, forming a duo of dependents with another hired hand named Ludwig (played by Ted Billings). Despite these differences, Karl wouldn't survive his movie, either, and meets a similar fate to Fritz at the hands of Dr. Frankenstein's monster.

Another notable role of Dwight Frye’s was in 1931’s Dracula as Renfield, the count’s brainwashed servant. Renfield bears little similarity to Fritz or Karl, but as if by transitive property through Frye, managed to significantly contribute to the "Igor" archetype. In the movie, Renfield frequently calls Dracula his "master," a very specific word that has wormed its way into how an "Igor" addresses his employer. Frye’s slow, breathy speaking style as Renfield has even become one of "Igor’s" standard voices (the others being either feral growls and yelps, or a Peter Lorre impression, with more on that to come). Greg Proops as Igor channels all of these attributes in the Whose Line sketch above: the voice, the language, and the excessive flattery. "A triumph, master! A testament to your genius, master!"

In the early days of Frankenstein films, Dwight Frye’s various performances acted as the first depictions of "Igor" still relevant today. His turns as Fritz, Karl, and Renfield made Dwight Frye the first iconic "Igor" in the same way that Boris Karloff became the first iconic monster. Still, there's two more notable "Igors" from the silent era who predate Renfield and Fritz both. Rex Ingram's 1926 feature The Magician starred Paul Wegener (famous for his German Expressionist films) as Oliver Haddo, an alchemist and hypnotist who requires blood from the heart of a noble maiden in order to create life. Haddo is assisted in this endeavor by an unnamed but hunchbacked servant played by Henry Wilson. The climax of The Magician foreshadows the revival scene from Frankenstein in many ways, right down to the hunchbacked servant descending a gigantic spiral staircase while desperate visitors pound on the castle door in a rainstorm. Predating The Magician by one year is The Monster, a horror-comedy directed by Roland West, in which a mad surgeon played by Lon Chaney lures victims to his sanitarium for experiments with transferring souls between bodies. Like Frankenstein, The Monster was based on a play, by Crane Weber. What is most interesting about The Monster for our purposes is that Dr. Ziska has several assistants to capture his victims for him and assist in his laboratory. One of these assistants is a bug-eyed, grinning, and gangly fellow in a cloak and hood named...Rigo!? That's right, not Igor exactly, but Rigo, played by George Austin. The fact that what may be the earliest film version of the "Igor" archetype is an anagram of Igor is such a tease: so close, yet so far, and trust me, we have a long way to go until we find a true Igor: a hunchback, an assistant to Dr. Frankenstein, and having the letters in his name in the right order. Although Dwight Frye wouldn't return for it, we would get a little bit closer in the third film in the Universal series, 1938’s Son of Frankenstein.