WHY WE BELIEVED IN THE BLAIR WITCH (AND WHY WE CAN'T ANYMORE)1

October 3, 2018 | Essays

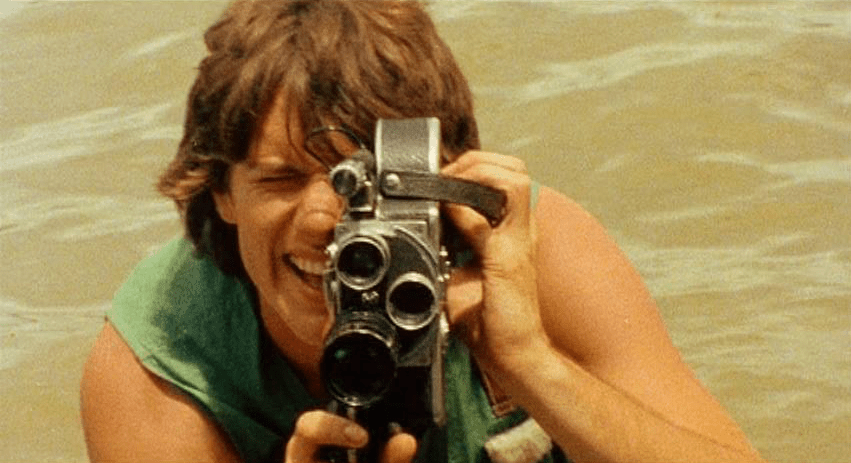

France, 1981: the Italian film Cannibal Holocaust is released to theaters and the magazine Photo claims that its depictions of butchery were real. Its director Ruggero Deodato is brought before French courts to disprove the allegation and to explain why the film’s cast have been suspiciously absent from the public eye. Deodato acquiesces and produces his actors, revealing that they had agreed not to appear in other media for one year to preserve his film’s illusion of authenticity—an illusion that was perhaps too successful if it landed him in a French court, and an illusion that worked only because Cannibal Holocaust wasn’t a conventional movie. Instead, it allegedly depicted what was recovered from the expedition of a doomed documentary crew filming cannibal tribes in the Amazon rainforest: “found footage.”

Found footage filmmaking is hardly as niche or novel today as it was in the early 1980s. From hits like Paranormal Activity and Cloverfield and genre deviations like Chronicle and Project X, found footage exists—for better or worse—in abundance. A side effect of this growth in popularity was that found footage films eventually did become conventional movies. Audiences were gradually inculcated to the techniques of found footage, and media literate audiences today aren’t naïve enough to believe that theatrically released shaky-cam footage of scared kids running through the woods is real. The last time that they were was when shaky-cam footage of scared kids running through the woods was theatrically released alongside The Phantom Menace, and The Blair Witch Project ushered found footage into the mainstream for the first time.

The Blair Witch Project.

●○○○○

The Blair Witch Project is the allegedly recovered footage of three amateur filmmakers who got lost in the woods of Burkittsville, Maryland while making a documentary about its eponymous folkloric crone. Despite sounding like a droll outlier in a blockbuster-packed summer season, there was a secret to its success: one of the first and greatest viral marketing campaigns in internet history. By the time The Blair Witch Project saw a wide release, details and rumors about the film had been spread onto internet message boards, leading people to believe in the Blair Witch and the film’s subjects being actual missing persons.

The nascent internet had yet to be corralled into the neat timelines and curated, familiar feeds we’re used to today. This was before Twitter, Facebook, and Wikipedia—hell, before MySpace and Friendster. Google was just learning to walk. Snopes existed, but focused mostly on hoaxes and scams circulated widely through e-mail. If you saw something strange on the internet—something mysterious, or even frightening—there wasn’t really anywhere that you could go to have it instantly explained or disproven to you.

It was in this context that The Blair Witch Project established its website, which was not a mere advertisement but a portal for furthering the narrative of the film-as-an-artifact (an important difference from the narrative of the film itself) by providing backstory, context, and more insight into the footage that was "found" in the Burkittsville woods. It featured diary entries from one of the "missing" filmmakers, photos of the site where the footage was "recovered," interviews with people involved in the "search"—all presented as not just "evidence" that not just "proves" the events of the film, but also provides a credible backstory for it in the first place.

This backstory was further expanded upon in The Curse of the Blair Witch, a companion mockumentary made for the Sci-Fi Channel. Like the website, it utilized excerpts and stills from The Blair Witch Project as "evidence" and framed them between interviews with people who were supposedly connected to the missing filmmakers, but it focused primarily on grounding the larger Blair Witch legend in historical reality. Documents attributed to colonial Blair were read in voice-over by actors in cliché historical affects. Archival footage related to the Blair Witch legend is peppered throughout and appears appropriately degraded for its alleged age. A 1971 clip from Mystic Occurrences (an aping of Unsolved Mysteries-esque shows) is dense with film grain, and footage of a press conference from 1940 has audio so fuzzy that it can barely be understood. These artificial artifacts brought to credible life the timeline illustrated on the Blair Witch website.

●●○○○

Although essentially everything about the Blair Witch itself was conjured whole cloth by the filmmakers, the key to its verisimilitude was that The Blair Witch Project and its adjunct promotional material very strategically based their most easily identifiable aspects in true reality. The subjects of The Blair Witch Project use their real-life names, for example, and they interview real-life residents of Burkittsville about the eponymous crone while shooting their documentary. The Blair Witch, as an alleged historical legend, was completely fabricated—yet some townsfolk thought that they had in fact heard of it before, or even had their own stories about it (though whether they were just improvising to make the best of their chance at getting in a movie is an enriching, rather than compromising, possibility for the collective construction of the "legend"). The website for The Blair Witch Project and The Curse of the Blair Witch were designed to be as thorough and deliberate pastiches of actual credible media as possible, to where even if one didn’t believe The Blair Witch Project was real per se, they may still think it was fiction based on the actual Blair Witch legend—a completely and utterly bogus legend, of course. Note that Burkittsville is in New England, which is a very smart setting in which to invent a plausible legend about a witch.

All of this elaborate artifice signifies titanic dedication and effort, but for what purpose? Why does it matter whether a found footage film possesses verisimilitude? Why can’t the technique just be used for stylistic reasons without going out of its way to be deceptive?

Well, these are fair questions, and I have a fair, if opinionated answer: it’s exciting. Found footage films that put the effort into verisimilitude, lore, and plausibility do something that no other films do, which is afford you the possibility of believing in it. One doesn’t watch Friday the 13th and think that it’s real because it doesn’t try to look real; even if the events of the film were real, it would have been impossible for the actual footage of the film to be, what with its Hollywood slickness and conventional aesthetics.

That’s why the found footage format lends itself so well to the horror genre: we’ve been telling each other monster stories for ages, and found footage horror films don’t just function as horror stories but can appear as evidence of those stories. A good found footage film will, at the very least, have us playing along and enjoying the possibility of "if it happened, this is what it would look like." But a great found footage film is one that is so convincing that you’re not even sure if it’s a matter of "would." A great found footage film tells you, "this is what it looks like," and has you watching with too little evidence to argue or imagine otherwise.

The Blair Witch Project.

●●●○○

In an interview with The A.V. Club in the summer of 1999, The Blair Witch Project directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez said that they "didn’t want to tell people that it was real, but [they] didn’t want to tell people it was fake, either" and that it was "enticing for [them] to entertain the thought of people…seeing [the film] for what it is and believing what’s going on until they see the credits roll at the end." True to their word, that is unfortunately where The Blair Witch Project breaks kayfabe. White text on a black background reveals that it was written and directed, credits its subjects as "starring" in the film, and obliterates all lingering doubt with an explicit disclaimer that "the content of this motion picture, including all characters and elements hereof is entirely fictional." Similar credits appear at the end of The Curse of the Blair Witch.

Just by crediting the people who made these films, by so much as hinting that the people portrayed in the film were not who they seemed to be or that they weren’t the only ones involved in its production, The Blair Witch Project and its peripheries implode on themselves. However, there was one more obvious aspect about these films that was working against them from the start: if the footage was real, why on earth would what amounts to a tragic snuff film be distributed by a major studio, let alone screened in mainstream theaters? Did people learn nothing from Cannibal Holocaust?

Despite the verisimilitude of the film-as-an-artifact, the necessary disclosures and standard practices of mainstream film production, distribution, and exhibition meant that at some point or another, the illusion had to be shattered. There wasn’t just a sequel in 2000, but an indulgent remake in 2016 (to which blairwitch.com became rededicated, with a link to the original site buried in its "About" page2). If a film truly wants to maintain its verisimilitude, how does it do so during its exhibition and distribution, and how can it hook post-Blair Witch audiences who are too savvy to be fooled by found footage so easily?

Well, it’s simple: you don’t release it theatrically, you distribute your film by chucking VHS tapes of it out of your car window in Baltimore. And you go back in time.

Cannibal Holocaust.

●●●●○

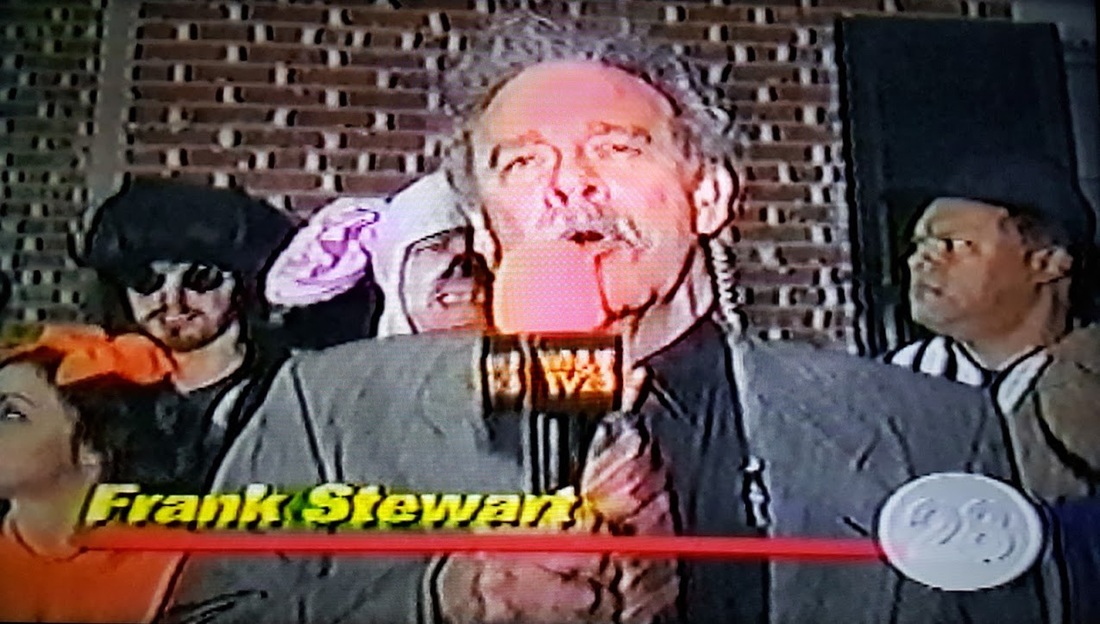

Anyway—on a completely unrelated note—a few years ago I became aware of "The WNUF Halloween Special," which was aired on a local news channel somewhere in the northeast on October 31, 1987. On that fateful night, a bold, ratings-grabbing attempt at a live on-air exorcism at an allegedly haunted house went awry somehow, and no official footage of that broadcast survived.

What has survived, though, is a bootleg-of-a-bootleg of the broadcast, taped from a viewer’s television on that very same night. That footage contains the broadcast in its entirety, including the evening news and even those obnoxious and hyperlocal commercials that feel so endemically late-eighties. That footage is grainy, garbled, and shows every sign of being shot on television cameras of the time (because it was) and being copied from multiple generations of VHS tape (because it was). That footage never saw the inside of a theater; copies of it just mysteriously appeared at VHS conventions and on the streets of Baltimore in 2013. That footage has no studio-mandated logos, credits, or disclaimers, because why would it? It’s an old news broadcast, not a major motion picture3.

That is what you should tell people when you tell them about this tape. Seek it out if you dare—I recommend either a VHS copy or the sketchiest online source you know. Make sure that anyone you’re watching it with knows its lore and nothing else. Watch them as they watch it. Watch their eyes. Play along, and even if it’s just for a brief and naïve moment, you and your friends can believe in something strange, mysterious, and frightening.

Or you can watch The Scooby-Doo Project. Zoinks!

The WNUF Halloween Special.

●●●●●

1This feature, my first ever paid piece of writing, was originally published on the now-defunct VRV Blog on October 3, 2018, and is republished here on August 30, 2021 with only mild revisions and the addition of these three notes.

2At a certain point, the blairwitch.com domain and all of its associated domains became defunct, and both the 2016-era website dedicated to the remake and the original 1999-era website have been lost to the digital ether, except for where archived versions exist.

3Admittedly, The WNUF Halloween Special has become a bit more mainstream since this piece was originally written. It is available for streaming on Shudder, has a crowdfunded sequel in production (at least as of September 2020, having suffered delays from the COVID-19 pandemic), and has in fact been screened in theaters like Alamo Drafthouse. Perhaps in writing a feature like this, I was (and still am!) complicit in that mainstreaming, and it's bittersweet: more people than ever know about this fun Halloween movie, and more people than ever can relish its dedication to technical verisimilitude and resultant craftsmanship, but that means fewer people that get to experience the film as an artifact. It only becomes a film.